Hermann Göring’s Luftwaffe and the $6 billion deal

How the unlikely combination of WWII Germany, a modest English engineer who created a worker’s paradise, an ambitious industrialist prosecuted as a traitor and a hardworking PhD helped build modern Norway, one aluminium ingot at a time.

The lightning-fast occupation of Norway by Nazi Germany in 1940 stunned the world — what strategic advantage could this little country on the northern fringe of Europe offer Hitler and his stormtroopers?

The simple answer, historians say, is that Hitler was mainly interested in securing Norwegian ports to access neutral Sweden and its vast iron ore deposits, which the Fürher desperately needed.

Hitler (left) and Field Marshall Hermann Göring at the Wolf’s Lair. Photo: Bundesarchiv, Bild 101III-Reprich-012-08 / Reprich / CC-BY-SA 3.0

But Field Marshall Hermann Göring saw another strategic advantage to the occupation, said Hans Otto Frøland, a professor in contemporary European history at NTNU and a member of the Fate of Nations research group.

“To understand this, we have to take account of the fact that aluminium had become a strategic metal. If you want to win the war, you have to control the air, and to control the air you need airplanes and to produce airplanes, you need aluminium and other light metals, and to produce aluminium, you need energy. And Norway had a lot of energy,” Frøland said in the latest episode of NTNU’s English-language podcast, 63 Degrees North.

Frøland has combed through public documents, company records, private letters and newspaper articles to put together the economic history of aluminium in Norway.

If you want to win the war, you have to control the air, and to control the air you need airplanes and to produce airplanes, you need aluminium.

It’s a story of a new nation trying to find its way in the global economy, brilliant engineers who found themselves forced into an uncomfortable alliance with Nazi Germany, British transplants who early on built worker welfare into their industrial planning, and a young NTNU graduate who after 24 years, took the helm of his company and transformed it into a global giant.

Turning falling water into energy

The source of Norway’s energy was its unusual geography: steep rugged coastal mountains laced with abundant waterfalls. The power of that falling water could turn turbines to generate electricity. Beginning at the turn of the 20th century, when Norway was newly independent country, falling water was seen as the key to building a modern nation.

There was one law that called the panic law because so many foreigners came to Norway to buy up waterfalls cheap.

At the same time, industrial growth in Europe and North America had developers on the lookout for places — like Norway — with ample, but underdeveloped, natural resources.

AS Stangfjorden Elektrokemiske Fabriker was established in 1897 and originally produced iodine and peat coal. In 1906 the factory was bought by the British Aluminium Company (BACO), who turned it into the first aluminium factory in Scandinavia. Photo: Paul Stang/Fylkesarkiv i Vestlandet

Norway didn’t have the ore needed to make aluminium — that could be transported by ship. The best place to use what Norway did offer — hydropower — was where the power was generated.

So companies began flocking to Norway to buy up the rights to waterfalls so that they could establish aluminium smelters or other energy-demanding industries. In 1906, the new Norwegian government, just a year old, responded.

“There was one law that called the panic law because so many foreigners came to Norway to buy up waterfalls cheap, because it was poor peasants who own these waterfalls, and they didn’t know the future value of it,” Frøland said.

Home-grown and international companies

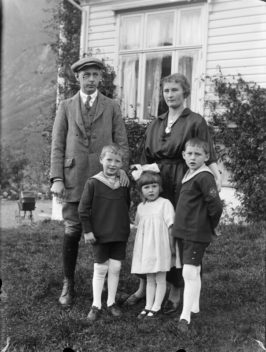

Director Maurice Russel Turner and wife Aslaug with their children Per, Sylvia and John (b.1913). Maurice came to Stangfjorden in 1910 as a chemical engineer. In 1911 he became director of the aluminium smelter until 1940 when Germany occupied Norway. With the outbreak of World War 2 in Norway the Turners fled to England. Photo: Paul Stange/Fylkesarkiv i Vestlandet

Companies that did choose to invest in building smelters in Norway, like the British Aluminium Company, or BACO, often sent their own employees to work at the facilities. One such employee, Maurice Russel Turner, married a Norwegian woman.

He subsequently helped develop the small town where the smelter he managed was located, and pushed his employer, BACO, to act when local farmers felt some of the environmental consequences of living near the smelter.

Another Norwegian industrialist at this time, Sigurd Kloumann, was driven during the pre-war years to develop a home-grown aluminium industry, the Norwegian Aluminium Company, or NACO.

Both Turner and Kloumann had their lives upended when Hitler occupied Norway. One man escaped Norway with his life. The other cooperated with Göring to expand Norway’s fledgling aluminium industry and was later tried — but not convicted — for treason.

From failure to foundation

The ultimate irony in Göring’s plans for Norway’s aluminium industry is that they failed utterly.

Not only were Göring’s plans for Norwegian aluminium production wildly overoptimistic, the Allies began bombing industrial sites in Norway to curb the production of materials for Germany. The photo caption says: Two years to build, four minutes to destroy. Bombs fell on huge German magnesium plant at Heroya, Norway. Attack was timed to strike between shifts, reducing Norwegian casualties. Arrow marks arming point. (U.S. Air Force Number 26027AC) Photo: US National Archives and Records Administration.

“This programme was overstretched from the beginning and never produced a kilo of aluminium in Norway,” Frøland said.

The facilities that were built or expanded by the Germans in their failed efforts to produce aluminium did end up benefiting the Norwegian economy in the post war years, however.

In 1986, two of these plants would become an important part of one of Norway’s largest companies, Hydro.

The $6 billion deal

Hydro wasn’t always an aluminium company. The company’s industrial roots lay in the production of artificial fertilizer by extracting nitrogen from the air. This was another process made possible at the beginning of the 20th century by new technologies that required huge amounts of energy.

Hydro moved into aluminium production in the 1960s, and was also involved early on in oil and gas development on the Norwegian continental shelf. Other businesses that were added to the Hydro portfolio over the years included a chocolate producer, a giant fish farming company and pharmaceutical companies. These were eventually sold off beginning in the 1990s, with the spinoff of the company’s original industry, fertilizer production, in 2004.

Svein Richard Brandtzæg at a press conference in 2019 announcing his successor, Hilde Merete Aasheim, as CEO. Photo: Hydro/Anders Vindegg

In 2009, Svein Richard Brandtzæg took over as head of Hydro, which by this time was focused on aluminium and energy production. Brandtzæg had both an engineering degree and a PhD in chemistry from the Norwegian Institute of Technology, one of NTNU’s predecessors. Up until the time he took over as CEO of Hydro, his entire 24-year-long professional career had been at the company, working his way up the ladder in different departments.

In 2010, faced with plummeting aluminium prices and working to keep the company afloat, Brandtzæg decided to pursue a risky strategy — to negotiate a $6 billion deal with a Brazilian company, Vale, to purchase their enormous bauxite mine and alumina refinery, the raw materials from which aluminium is made.

If he succeeded, the deal would save Hydro. But the Brazilians weren’t so sure it was a good deal for them.

Hydro gets the raw material bauxite from their mines in Paragominas, Brazil. Bauxite is used in the production of alumina. Photo: Hydro/Halvor Molland

Things came to a head during April 2010, when the two CEOs met in London to try to come to an agreement. After four days of hard haggling, Brandtzæg realized the two companies were still too far apart, and he headed back to Norway.

Then, while he was in a taxi on the way to the airport, his phone rang.

To find out what happened next, however, you’ll have to listen to this episode of 63 Degrees North. You can find and subscribe to the podcast wherever you listen.