Tea bags — and more — on the tundra

Ever wonder how climate researchers know what they know? 63 Degrees North journeys to 69.5 degrees North to find the answer to that exact question.

I’m on a little plateau at the base of Iskoras mountain, a low peak in far northern Norway, outside of the town of Karasjok, about 1000 kilometers as the crow flies from Trondheim, and far above the Arctic Circle.

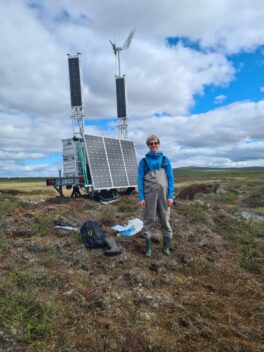

The Iskoras Mountain field site, where Hanna Lee, an associate professor at NTNU’s Department of Biology, has been studying how climate change is affecting the landscape. Photo: Nancy Bazilchuk

Getting to here from town requires an hour-long drive on rough dirt roads, and then another hour’s hike over a low ridge, to where I am now.

Hanna Lee walks into her field site at the base of Iskoras Mountain, outside of Karasjok. Photo: Nancy Bazilchuk/NTNU

Thawing permafrost and palsas mean that the researchers have had to build boardwalks to access the field site. It can be a wobbly, wet walk in. Rubber boots required, chest waders a bonus. Photo: Nancy Bazilchuk/NTNU

It’s early June, and quite windy and chilly. There aren’t a ton of trees here, just stunted birches with wispy little leaves that are so small they look like they’re not sure they want to open up in the weak sun.

There’s an idea that — and these are all hypotheses now — that when permafrost thaws, then there’s going to be rapid increase in CO2 and methane release.

In front of me is a weird bumpy depression filled with a crazy quilt of open water, grassy bits and little hillocks made out of peat. These little hills are called palsas, and inside there’s a core of ice.

Some of them are dry on the top and cracked open, wide open, like a crusty boil that has split.

Lisa van Solt and Daniel Serrano (in blue, back) take temperature measurements on a thawing palsa mound. Photo: Nancy Bazilchuk/NTNU

And wandering around, out in this mix of freezing water, bottomless mud, and wet peat is a young man wearing a pair of chest waders. He’s carrying a trowel and a bag filled with tea bags.

Tea bags in the service of climate science

Daniel Angulo Serrano, who worked as a field assistant on the Iskoras research site, outside of Karasjok, in the summer of 2022. Part of his field work included burying tea bags. Photos: Private

His name is Daniel Angulo Serrano.

And what kind of tea bags might these be?

“Lipton tea bags, green tea and rooibos exactly,” he says.

And he’s burying these tea bags. Lots of them. But how many?

“One hundred more or less? Probably a little bit more,” he explained on the latest episode of 63 Degrees North, NTNU’s English language podcast.

Daniel is not testing new ways to brew tea. Instead, his efforts are part of a larger study where a team of researchers is trying to solve the riddle of how global warming is affecting this landscape — and how those changes in turn might amplify future warming.

Secrets in the permafrost

In the summer of 2022, Daniel and his colleagues — Anja Greschkowiak, a PhD candidate at NTNU; Lisa van Solt, then a master’s student at Radboud University in the Netherlands; and Omar Granados, then a master’s student at Utrecht University in the Netherlands — were working on an ambitious long-term climate research project headed by Hanna Lee, an associate professor at NTNU’s Department of Biology.

Lisa van Solt (left), Daniel Serrano and Omar Granados do different measurements at the Iskoras Mountain field site. Photo: Nancy Bazilchuk

If we end up finding out that climate warming is actually emitting a lot of methane from thawing permafrost, then this means that we really have to cut down even more on our emissions.

“There’s an idea that — and these are all hypotheses now — that when permafrost thaws, then there’s going to be rapid increase in CO2 and methane release,” she said on the podcast episode.

Lisa van Solt, right, and Anja Greschkowiak make measurements from thawing permafrost. Photo: Nancy Bazilchuk/NTNU

Carbon dioxide, CO2, mainly produced by burning fossil fuels, is the main greenhouse gas causing the planet to warm. But methane, which is produced by microbes digesting rotting plants and famously, burping cows, is 30 times more potent than CO2 when it comes to warming the planet.

Trapping and measuring emissions

To figure out what is happening with CO2 and other greenhouse gasses, the researchers need to find ways to trap and measure the emissions from the permafrost that is thawing now — which explains the crazy quilt of tubes, pipes, little greenhouse chambers and instruments that are all over the field site.

Hanna Lee and a small greenhouse chamber on the Iskoras field site in northern Norway. The different wires, pipes and tubes are all part of the way that researchers study what’s happening to the permafrost in real time. The plexiglass chamber is designed to warm that patch of tundra by an extra 2 degrees C, so that researchers can see how the vegetation responds. Photo: Nancy Bazilchuk/NTNU

“I’m trying to quantify the importance of CO2 and methane emissions and uptake…. from the thawing period, and then even beyond, many hundreds years of thawing permafrost,” she said.

Have microphone with wind protector, will travel. Yes, that furry thing in front of my face is supposed to dampen wind noise. It didn’t work.Photo: Nancy Bazilchuk/NTNU

That matters because scientists need to know the amount of greenhouse gases that are being emitted by natural sources, in addition to manmade emissions, Lee said.

“If we end up finding out that, well, climate warming is actually emitting a lot of methane from thawing permafrost, then this means that we really have to cut down even more on our emissions. So that’s why it’s important to really understand the processes, what’s driving these things,” she said on the podcast.

Here’s a link to a video made in 2020 by Sasha Azanova, an artist and photographer based in Bergen.

September 2020: Finnmark from Sasha Azanova on Vimeo.

To hear more about Hanna Lee’s work on the tundra, and what those tea bags are all about, join me and listen to the latest episode of 63 Degrees North.