Colonization usurps indigenous languages

Up to 90 per cent of the world’s languages may disappear by the end of this century. Inuvialuktun is one of them.

The Inuvialuktun language is outstanding in its ability to describe nature in Canada. But Inuvialuktun is in danger.

“I can’t sit here as a researcher at NTNU and save the language of the Inuvialuit Settlement Region. But I can contribute to the work that the speakers of the language are doing,” says field linguist Signe Rix Berthelin at NTNU’s Department of Language and Literature.

Her contributions include creating grammar explanations and teaching materials that focus on the language’s syntax and structure.

Berthelin is actually working on a dissertation on abstract words such as “may, must and will”. Or “lla, hungnaq and ȓukȓau,” as they’re called in the Inuvialuktun language of western Arctic Canada.

Linguists are deeply interested in topics such as abstract words, and her doctoral thesis will be ready for Christmas. But for this interview she preferred to talk about how a language can be saved.

90 per cent could disappear

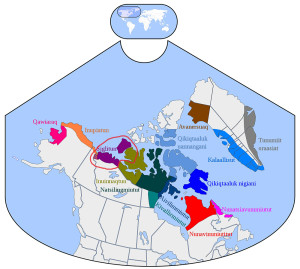

The map shows the distribution of Inuit language variants. Inuvialuktun is spoken in the northwesternmost part of Canada. Illustration: Wikipedia

It is surprisingly difficult to say what really makes a language its own independent tongue. Is Australian its own language? Are Serbian and Croatian separate languages, or is the distinction purely political? Norwegian Bokmål and Nynorsk each have their own Wiki pages and ardent supporters, but are really just different ways of writing the same language.

Young people and older folks may share the same dialect, but don’t necessarily speak the same way. Linguists refer to these differences as sociolects—or social dialects—which are associated with a social group.

“Sociolects, dialects and languages are important parts of our identity, how we express it, and how we understand the world around us. We give meaning to the world and our experiences through the way we speak. Each language is unique and has developed and adapted to the communities and social circles that surround the people who speak it,” says Berthelin.

The most common estimate is that there are approximately 6000-7000 languages in the world today. Between half and 90 per cent of them could disappear by the year 2100, according to the Cambridge Handbook of Endangered Languages.

The explanation for languages becoming endangered is often that the young members of the community don’t use the language. And the reason for this is closely related to colonial history.

Language must be passed on

Imagine if Norwegian were on the way out. Children around you speak more and more English while Norwegian is a language for the older generation. This is the reality in many cultures, and many people are working hard to nurture their threatened language and incorporate it into daily life.

Native tongues

UNESCO provides the following figures for speakers of Inuvialuktun:

- 240 speakers of Uummarmiutun. (Uummarmiutun also goes under the name Inupiatun due to its close relationship to Alaska's Inupiaq dialect.)

- 230 speakers of Siglitun.

- 890 speakers of Kangiryuarmiutun.

Figures are from 2001.

Inuvialuktun comprises three dialects that together have approximately 1500 speakers.

Berthelin has concentrated on the Uummarmiutun dialect, spoken in the far northwestern part of Canada near the border with Alaska. She has also looked at the Siglitun dialect.

Kangiryuarmiutun – which is closely related to the central Canadian Inuit dialects – is the third dialect, which Berthelin hopes to have the opportunity to research later.

The dialects comprising Inuvialuktun are distributed across northwestern Canada and are mutually intelligible. People in northern Alaska who speak Inupiatun can also understand Inuvialuktun.

Speakers of Inuit languages range from western Alaska to eastern Greenland. At the outer edges of the range, the languages are so different that people from the farthest east and farthest west need to speak slowly and clearly to understand each other if they meet and want to speak Inuit together.

“The youngest Inuvialuktun speakers working with me on the project are in their late 50s,” says the linguist, who recently returned from her second three-month stay in Inuvik in Canada’s Northwest Territories.

This is one of the main problems when a language becomes endangered. The youngest community members have less and less opportunity to learn the language, and when the elders are gone, it may be too late. A language can disappear completely in the course of two to three generations. The elders’ efforts to teach and pass on the language are essential.

Inuvialuktun has eager and competent language specialists and advocates, including the Inuvialuit Cultural Resource Centre. So the Inuvialuktun language may manage to survive.

Connected to nature

NTNU researcher Signe Rix Berthelin. “I can’t save the language of the Inuvialuit Settlement Region. But I can contribute to the work that is being done by speakers of the language,” she says.

Berthelin emphasizes that it is important for the language to be taught — so that the next generation learns it. Inuvialuktun is the language of instruction several times a week at school, and in middle and high school Inuvialuktun is an elective. Beyond the classroom learning, it is also important for students to get out in nature, since the understanding of the Inuvialuktun language and the understanding of nature and natural processes are so closely linked.

“People have spoken Inuvialuktun for thousands of years, and since the Inuit have such long experience in observing and understanding natural conditions and phenomena, the language is ideally suited to talking about that kind of thing. Not that we can’t talk about other things in Inuvialuktun, too,” says Berthelin.

The names of the months illustrate this connection to nature. For example, Hiqiññaatchiaq means “when the sun comes back” (January), and Kivgalungniarvik means “time to hunt muskrat” (March). You can see more of the months here.

Many elders are happy to bring youth out into the forest to show them the places, moods and creatures that are so closely tied to the Inuvialuit language, history and culture.

Strong involvement

One of Berthelin’s close partners is Vanessa Kasook, who is a research assistant and actively involved in the work for her language.

Kasook, along with Beverly Siliuyaq Amos and Shirley Mimirlina Elias, made a phrasebook of expressions that can be used in daily life. It includes phrases such as “Put on your shoes.” and “My God, calm down!”—designed to be useful for parents who want to use Inuvialuktun with their children. Kasook wanted to create a book like this to increase the prevalence of Inuvialuktun in homes, and thus contribute to the next generation knowing their language.

There are also technology-based teaching tools for children and youth who want to learn the language. A newly developed language app from the Inuvialuit Cultural Resource Centre is very popular. (See links at the bottom of this article.)

The centre works to preserve the language, among other things.

Berthelin says that residents in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region are working to nurture Inuvialuktun and keep it alive. They know their culture, their community and their history and therefore have the necessary expertise to revitalize the language.

“For me it’s more a question of what I can contribute,” says Berthelin. “I’m so lucky to have been allowed to come and study and research Inuvialuktun. So I’m happy to try and make myself a little useful,” she adds.

As a linguist, Berthelin can examine the structure of the language and help put together instructional materials that language teachers can use in evening Inuvialuktun grammar classes. More materials like this are on their way, but they take time and cost money.

She also helped to create an educational grammar reference, with explanations based on real stories told by Inuvialuit elders Panigavluk and Mangilaluk.

Sources and sponsors

Inuvialuit elders, who work with Signe: Panigavluk, Mangilaluk, Kavakłuk, Agnagullak, Suvvatchiaq and Mimirlina.

These institutions have helped to finance the work:

- NTNU Faculty of Humanities

- Ling Phil, Norwegian Graduate Researcher School in Linguistics and Philology

- Aurora Research Institute, Northwest Territories, Canada

- NTNU Department of Language and Literature

They shared their knowledge and stories in Inuvialuktun. The recordings were then analyzed grammatically and are now available online. Interested parties can listen to and read Inuvialuktun and see how the language is built up, by using translations that break down each word. That way they can learn the language through real stories told by Inuvialuit elders.

Word by word

Her main contribution to the language so far has been to arrange the stories she was told in a word-by-word fashion, in addition to compiling the pedagogical grammar explanations.

For example, a sentence is broken down as follows:

Uqauhira piqpagivialukkiga becomes:

Uqauhiq -ra: ‘Language, my ”

Piqpagi: “Love”

Vialuk: “Real”

Kiga, “I”, when pointing back on “it”

Altogether: ‘I love my language high’

This process is important for understanding a language, and especially younger people have shown interest in “zooming in” on their language this way.

The sentence comes from one of Panigavluk’s stories.

Panigavluk is one of the elders who is working hard for her language.

Colonialism

But why is Inuvialuktun endangered?

“Colonialism,” is Berthelin’s short answer.

English has taken over as the primary language among many of the Inuit in Canada. In Greenland, it has been Danish.

Inuit and First Nation children were previously sent away to boarding school by the Canadian government. They were gone for many years, received training in English, but not in their own language, culture and history. Many youngsters went several years without any contact with family and community life. This naturally left its mark on the society and on people’s lives. Some say that they feel a void, because they have lost a big part of their culture and language.

“Many children were beaten and bullied by teachers for speaking their language, and for being who they were,” says Berthelin.

This led to many adults later finding it uncomfortable to speak their own language.

“If you hear that your culture and your language aren’t worth anything for long enough, you start believing it,” says Berthelin.

Meanwhile, English was needed to succeed in mainstream society.

Berthelin says, “You can see a connection here with events in Norway. Not that many years ago, the Sami were sent to boarding school to learn Norwegian, and were told that their language wasn’t worth protecting.

Why?

But why should we protect all these languages? Isn’t it just as fine and hugely convenient for everyone to speak the same language?

“It is extremely important, partly because it’s about staying connected with one’s own culture and history,” says the linguist. “Also, some of the knowledge and intellectual heritage can be best formulated in Inuvialuktun.”

It is possible to be connected to the culture in other ways, such as through drum dancing or practicing other arts like leather sewing and embroidery. But the language is essential.

“I’ve noticed myself that I become more conscious that I am Danish when I do this work. Danish isn’t a threatened language, but the language gives me a sense of belonging somewhere,” she says.

Berthelin is not sure whether a language has to be used in daily life to be alive. There must always be some fluent speakers, so that someone can pass it on at any time. Not everyone has the time and possibility to learn the language fluently.

But even if most children in the area do not speak Inuvialuktun fluently, it is important that they know enough to feel a sense of belonging—for example, by being able to point to a seal and know that their ancestors called it natchiq, or by knowing the differences between the various processes in nature, or the different types of snow.

Inuvialuktun has an especially rich vocabulary for these areas. Once you know this vocabulary, you can more easily understand the knowledge that is connected to different animals and other essential elements of nature.

Thriving in Inuvik

Berthelin has supervisors at both the University of Toronto and the University of Copenhagen. But her head supervisor is Professor Kaja Borthen at NTNU.

“Researching an endangered language is a special research assignment that demands particular ethical guidelines,” says professor Borthen.

For many doctoral students, acquiring international contacts and publishing in major journals are most important. But that’s not necessarily the best path if you want to do a proper job as a field linguist. In that case, it’s important to become acquainted with people who speak and are learning the language.

Getting to know people “is one of the best parts of the job,” says Berthelin. “I get to spend time with cool older women, who generously share their wisdom and experience. As a young woman, this is very valuable to me personally.”

Borthen commends Berthelin because she prioritizes giving popular scientific lectures and developing educational texts on Inuvialuktun over just attending scientific conferences. International publications are important, but ultimately they are perhaps more important for the researcher’s career than for society.

“It’s pointless to present a 300-page doctoral thesis or a heavily theoretical scientific article that takes two or three years to get proofread, peer reviewed and published to the local population. The knowledge needs to be passed on now. To those it makes a difference to,” says Borthen.

However, the two are not mutually exclusive. Berthelin has also published scientific papers. But engaging with the local community to work on their language is a direct contribution. It ensures that the relevant local community can access and use the research findings.

Sources:

This page provides more information about Inuvialuktun language and culture.

Read more about the different dialects.