Blood, banishment and a 500-year split

A series of bloody religious wars were fought after a Church divide that Martin Luther did not originally want. How did it all go so wrong?

PROTESTANT REFORMATION: This year marks 500 years since Martin Luther openly criticized the Catholic Church. It was the beginning of a movement that eventually saw the church split in several directions. But religious issues were not the only area of disagreement.

The Reformation

- October 31, 2017 marks the 500th anniversary of the beginning of the Reformation, when Martin Luther first made his criticisms of the Catholic Church public.

- Gemini is marking this event by publishing several articles about research on the Reformation.

- Professor Ola Tjørhom has edited a book

(in Norwegian) entitled «Reformasjonen i nytt lys (The Reformation in a new light)» along with Professor Tarald Rasmussen at the University of Oslo. The Arne Bugge Amundsen, Aud Tønnessen and Hallgeir Elstad, who all study religion, also contributed to the book.

“The political situation was crucial in triggering the split,” says Ola Tjørhom, Professor Dr. theol. in NTNU’s Department of Teacher Education.

That is, a very worldly power struggle was actually the main reason matters escalated to the point that the one western Church became fractured.

Cain killed Abel. Brothers went to war against each other. Engravings from a German Martin Luther Bible from roughly 1702. Photo: Thinkstock

“Differences in learning and theology naturally played a decisive role, but they came later, in a way, and just cemented the political divide,” says Tjørhom.

So it wasn’t really a religious split – at least not exclusively so.

- You might also like: The church revolution that changed Europe

Tried to reach agreement

From the outset, Lutheran reformers saw themselves as a renewal movement and as a “religion party” within the Catholic Church.

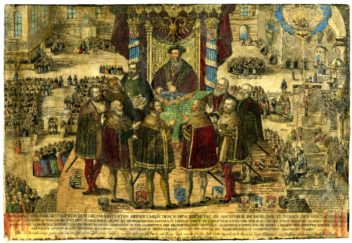

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor wanted to end the disagreement between the parties, but chose the Catholic side for practical reasons. Illustration: Jakob Seisenegger

Needless to say, the Pope was not particularly enthusiastic about the opposition in Germany, and at the time he had a significant army. Luther’s followers found support and protection from German princes, especially in northern Germany.

It is safe to say that Martin Luther was not only a man who sought compromise. Already in 1520, the Pope sent a papal bull threatening to banish him.

Soon afterward, when Luther nonetheless went ahead and publicly burned the Pope’s edict, along with some other Catholic writings, the Pope did finally excommunicate him. Luther then fled and lived in hiding for extended periods.

Evangelical followers, however, continued to try to find compromises with the Pope for years. Although the tone was very conciliatory to begin with, all these efforts fell apart in the summer of 1530.

Augsburg Confession

The Church must be “brought back to one simple truth and Christian concord, that for the future one pure and true religion may be embraced and maintained by us, that as we all are under one Christ and do battle under Him, so we may be able also to live in unity and concord in the one Christian Church.”

This excerpt from the Augsburg Confession, or Confessio Augustana, later became the most important confession of faith of Lutheranism. But at that time it was just as much a necessary statement of defence and an attempt to document unity with the Catholic tradition.

The Confession was presented at the Diet of Augsburg in 1530. The mighty Holy Roman Emperor Charles V wanted to put an end to the conflict between the evangelical reformers and the Catholics, and invited the parties to present their views.

“The Confessio Augustana was an open and unified statement of opposition to the Catholic Church, but in my opinion it included several tactically justified condemnations against the Anabaptists and radical wings of the Reformation,” Tjørhom says.

The Reformation had already split in many different directions. In order to reach a consensus with the Pope in Rome, more moderate Lutherans were willing to go quite far in criticizing the most extreme groups.

The Augsburg Confession was written by Luther’s colleague Philipp Melanchthon. As an outlaw of the Empire, Luther was at that time safely ensconced in Coburg Fortress in Bavaria – today a three hour drive or an SMS away from Augsburg, but in those days a much more impractical distance to travel or communicate from.

Failed to achieve peaceful solution

Things did not go quite as Melanchthon and his men had wished. The reconciliation proposal failed.

The Pope’s emissaries were led by Johannes Eck. They formulated a papal response to Augustana called the Confutatio. Parts of the text were relatively moderate, but were nevertheless largely a rejection of the evangelical teachings.

Emperor Charles V signed onto the papal response and demanded that the Lutheran reform groups do the same. He wanted to put an end to all this discussion, partly because the parties had not found any common solutions to what the Augsburg Confession refers to as the Church’s “abuse” and which, according to the evangelical theologians, was the main cause of disagreement.

Peace of Augsburg in 1555. The parties agree. The princes are given the power to decide the religion of their subjects, and in practice, religious groups must live in different areas. Illustration: Johann Dürr, The British Museum

“If they had reached a resolution, it’s conceivable that the Reformation and the split of the Church might have taken quite a different course,” said Tjørhom.

Sharper divide

But the Emperor had plenty of secular concerns as well. The Ottoman Empire, with its core area in today’s Turkey, was making steady progress towards Europe. At that time, the Pope did not only have spiritual power, but also worldly and military power as the sovereign monarch in the Church State.

“The Emperor wanted to unify the kingdom in the war against the Ottomans and considered religious unity to be the ideological basis for political-military unity,” said Tjørhom.

The Emperor chose political alliance with the Pope and his army over concern for the Reformers. Worldly power was apparently more important than spiritual power. The Ottomans had to be stopped. He had to have unity. But that’s not how things happened.

Perhaps the Emperor didn’t anticipate the reaction of the Protestants. They were not giving up. Instead, the divide was sharpening.

“The tension between religious parties escalated because they had different alliance partners with conflicting interests,” says Tjørhom.

The Emperor and the Pope were both central authorities with common goals despite their intense rivalry. The Protestant congregations sought support from sympathetic German princes, who had strong regional preferences and interests. These princes had great influence.

“At that time there was no centralized Holy Roman Empire. The Emperor had certain national institutions, but the strongest state growth took place at the regional level under the Emperor,” says Professor Erik Opsahl at NTNU’sDepartment of Historical Studies.

The defensive alliance

In order to create a counterweight to the Emperor and the Pope, German princes and the Protestant churches formed the Schmalkaldic League in 1531. This was a military alliance where one of the prerequisites was that members were aligned with the reformist teachings.

Initially, Charles V was not particularly keen to come into conflict with this league. For long periods during his 37 years on the throne, he was either engaged in war or preparing for war, and at this time he was most concerned with the Ottomans and the French.

The number of Luther’s followers in Germany was growing, and German Lutheran princes were becoming stronger and entering into alliances with different parties that suited them best. But since this was also a battle for worldly power, the situation became an open battle as soon as the Emperor had an opportunity.

Peace with the French was achieved in 1544, and in 1545 with the Ottomans. The Emperor was then able to devote more attention to the religious outbreaks in Germany, leading to the Schmalkaldic War from 1546 to 1547.

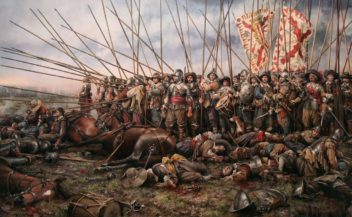

XVI century, council at Schmalkaldik war time (1546-1547), conflict between the forces of Emperor Charles V and the Lutheran Schmalkaldic League. The bucolic atmosphere in the illustration shouldn’t mislead: the Schmalkaldik war was a comparatively brief but rather bloody episode of the warfare following to the Lutheran Reformation and allegedly caused by it.

The German princes had a significant army, but allegedly useless military leaders. The Emperor routed the princely houses at the Battle of Mühlberg in 1547.

But not even this major military setback was enough to put a halt to the hostilities.

In 1552, Protestant troops drove the Emperor to flee, and his brother Ferdinand had to negotiate with the opponents and agree to major concessions. A lasting peace came in 1555, and this is what finally led to a permanently divided church.

- You might also like: Indulgence trading was big business during the Reformation

Religious peace reinforced the split

“The religious Peace of Augsburg in 1555 played a key role in the process towards the division of the Church,” says Tjørhom.

That year, the Schmalkaldic League and the Emperor met again to reach a lasting peace. The German princes had fought for and obtained a good starting point, and the peace that followed lasted more or less until the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War in 1618, but not without a price.

“The peace rested on the fundamental principle that the religion of the prince determines the people’s religion,” says Tjørhom.

When the leader in a region decided what you had to believe, it meant that Lutherans in a Catholic region had only two choices – either convert or emigrate. The reverse also held true.

“The Peace of Augsburg excluded the possibility for different churches – Catholic, Lutheran, and later Reformed traditions – to exist side by side within the same region or nation. The regional division contributed decisively to a formalized, organizational church divide,” Tjørhom says.

Larger belief differences

At the same time religious confessionalization, or “confession-building,” took place, clarifying “this is what we believe, this is what the others believe and the others are wrong.”

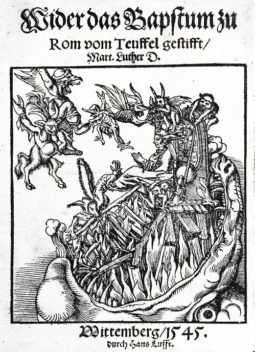

Towards the end of his life, Martin Luther published his last and most bitter writing Against the Papacy at Rome, Founded by the Devil. Illustration: Lucas Cranach the elder

“For the Catholic Church, this happened primarily through the Council of Trent from 1545 to 1563 and focused on stopping the emerging Protestantism,” says Tjørhom.

Early modern Catholicism was not solely reactionary, according to Tjørhom. It also contained several renewal impulses and approaches. But these were eventually abandoned in favour of a strong centralized Catholicism under the control of the Pope.

The Lutheran orthodoxy had its golden period between 1550 and 1650 and was also an expression of massive confessionalization. Each confession demonized the teachings of the other, and neglected anything that could create a basis for unity.

Luther died in 1546. He had become increasingly bitter in his relationship with the Pope, and towards the end of his life wrote his most vehement and vulgar treatise, “Against the Papacy at Rome Founded by the Devil”, which is formulated just like it sounds.

Millions lost their lives

The distinction between religion and politics is rarely clear. Religion is seldom the cause of religious wars.

But the divide between Protestants and Catholics was at least part of the cause of the German Peasants’ War, the Schmalkaldic War, the Eighty Years’ War in the Netherlands, several wars on the British Isles, French religious wars and the Thirty Years’ War.

“During the Thirty Years’ War war, Catholic France supported the German Protestants against the Catholic Holy Roman Emperor from a political-strategic standpoint. Political considerations could thus override religion,” says Opsahl.

It is impossible to know exactly how many deaths resulted from all these disputes, but these early wars, by even the lowest estimates, led to of more than five million deaths due to acts of war, massacres, genocide, disease and hunger.

Into modern times

During the Thirty Years’ War, religious parties banded together somewhat across denominations. Here from the Battle of Rocroi. Painting: Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau (Click name for link to artist)

The Peace of Westphalia effectively ended the Thirty Years’ War, during which Catholics and Protestants had made some alliances.

“The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 essentially continued the 1555 Peace of Augsburg,” says Tjørhom.

Religious freedom was now extended to include followers of the Reformed teachings of Huldrych Zwingli and Jean Calvin. But the church principle that provided for the religion of the prince to become the religion of an area and its inhabitants basically continued.

Peaceful relations between Catholics and Protestants are fortunately more the norm now than they were then. But even 500 years later there are few, if any, signs that the two confessions will unite in a common doctrine.