An Italian agricultural community seen through a 50-year-old looking glass

Fifty years ago an anthropologist studied and described an Italian agricultural community that was characterized by poverty, the Mafia and vendettas. Now his anthropological dissertation has been translated into Italian and is helping the community to understand themselves better.

About 50 years ago, Jan Brøgger received a university stipend. He bought an old Volvo and headed to Southern Italy with his wife and twin four-year-old daughters. He had heard that a Greek-speaking people lived in the area of Calabria in Aspromonte, in Southern Italy.

Brøgger, who later became one of Norway’s most famous social anthropologists, had dreamed of studying a small Italian village. The family settled in the mountain village of Bova Superiore, a small community that hung onto the steep incline at 900 meters above sea level.

Often it’s not easy for researchers to gain the confidence of the people or group to be studied, and young Brøgger also found this to be the case for his work.

In his book Folk uten land [People without a country], Brøgger wrote in the chapter about the Greek minority in Aspromonte:

“One day there came a knock on the door of the house we had rented. ‘My name is Pietro Varese, and my mother asked me to give you this bottle of wine.’”

Then the boy left. Once Brøgger figured out the unwritten rules around the local custom of giving and receiving gifts, the ice was broken.

Studied the peasants

During the months that Brøgger and his family lived in Bova, Brøgger immersed himself in the lives of the peasant farmers. They were amazed that Brøgger and his wife Bodil were more interested in socializing with them than with the landowners, bureaucrats and intellectuals they would traditionally be expected to associate with. This society had strong class divisions, and the peasants were at the bottom.

Jan Brøgger was quickly dubbed il professore in this peasant community, even though he was still a student at the time and gathering material for his doctorate.

The Brøgger and Varese families formed a strong connection and have had a close friendship over many years since.

Wanted study translated into Italian

Brøgger’s fieldwork in Bova Superiore was the basis for his doctoral dissertation: Montevarese. A Study of Peasant Society and Culture in Southern Italy.

Three years ago, the Swiss social anthropologist Moritz Grasenack became aware of Brøgger’s dissertation in English. He wanted to have it translated it into Italian. Since Jan Brøgger died in 2006, Grasenack contacted NTNU’s Department of Social Anthropology, who put him in touch with Brøgger’s widow Bodil.

The Italian version of the book was released in May of this year. The book includes additional chapters by Bodil Brøgger of her personal memories, and by Pietro Varese, who 50 years earlier was the young boy who delivered the welcome gift to the anthropologist’s family. A chapter from the book Folk uten land [People without a country], written by Jan Brøgger after a return visit to Calabria 40 years later, was also included in the Italian version.

Moritz Grasenack edited the book, and the Italian social anthropologist Giuseppe Ciancia translated it.

Available to the people it’s all about

Recently, Grasenack and Ciancia visited NTNU in Trondheim in connection with a seminar at the Department of Social Anthropology and an exhibition at the NTNU University Library with pictures and text from Brøgger’s fieldwork.

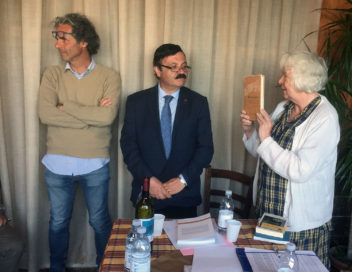

Bodil Brøgger presents Jan Brøgger’s work on Bova to the Mayor of Bova in May 2017. Translator Giuseppe Ciancia appears on the left. Photo: Harald Aspen

Grasenack was motivated to make Brøgger’s historical, ethnographic description of a rural community in the late 60s available to the very people it was about – the Bova residents studied and their descendants.

“Reading about their society 50 years ago and comparing it to the present day can give people a deeper understanding of why things are as they are, and why people react and feel as they do,” Grasenack says.

“They’re able to better understand the modern society they’re living in now, because they recognize some of the traits – like mentality, rank and ways of interacting – described in the 50-year-old dissertation. So the ethnographic, and now historical, study can be a tool to understand themselves better.

Most residents recognize their community in the descriptions of rural life. But they’ve also found some facts to argue about, especially around family relationships. One woman mentioned in the book – who remains nameless, of course – aroused great interest.

Not everyone was happy about the book release. Some people may be ashamed because, coming from a premodern community, they were seen as “primitive” and inferior. And those feelings of inferiority, honour and shame hang on even though current residents are part of a modern society now.

Speaking Greek for the tourists

Jan Brøgger (1936-2006) was Professor of Social Anthropology from the time he moved to Trondheim and established what is now called the Department of Social Anthropology at NTNU, until he died in 2006.

Giuseppe Ciancia says that Bova Superiore has changed a lot in the last 50 years. Historically, it was an agricultural community that survived by producing wine, cultivating olives and grains, and raising livestock on the hilly mountain slopes that are 900-1000 m above sea level. Self-sufficiency and shared community work formed the basis of people’s livelihoods, and money wasn’t used much. Nowadays Bova has grown into a modern society. Few livestock farmers remain, the sheep wander everywhere, but nobody cares. To the extent that farming still exists, it relies on hired Indian workers and cheap refugee labour.

And now tourism has taken over the region.

“It used to be people were ashamed to speak Greek because it was regarded as an inferior peasant language. Now Greek has been hyped up, despite the fact that it’s hardly used anymore,” says Ciancia.

This Greek renaissance is probably mostly a show for the tourists. But people now seem proud of their Greek origins that they wouldn’t admit to before.

Grasenack calls the Greek resurgence an “act” that today’s government officials are taking advantage of. What was previously associated with peasants and landless people has now become part of the official narrative, and is mentioned at every opportunity.

“The people of Calabria are still poor and still feel like second-class citizens, like they did when Professor Brøgger did his fieldwork there,” say Grasenack. “Honour, shame and power, the Mafia (N’Drangheta) and vendettas still characterize the villages, and its high murder rates make it one of the most violent areas in Europe,” he adds.

Atoned for his brother

The Brøgger and Varese families had close contact during the fieldwork and maintained friendship for many years afterwards. Pietro Varese was a boy at the time. Here he is pictured in front of the poster with the image of himself (the boy on the donkey) at the release of the Italian version of Montevarese in May this year. Photo: Harald Aspen

Pietro Varese was the son of one of Jan Brøgger’s most important informants during his fieldwork. Pietro’s brother came to blows with someone over a girl, and ended up killing him. The brother fled, and Pietro was arrested because he belonged to the family. Pietro took the blame and sat in jail for 16 years.

“He was fine with that – it was a kind of honour for him to pay for his brother’s atrocity,” says Harald Aspen, associate professor at NTNU’s Department of Social Anthropology. Aspen travelled to Italy with Bodil Brøgger for the book launch in May this year.

“After Pietro got out of jail he joined the Jehovah’s Witnesses and moved to Switzerland. He said he had two choices: either joining the Mafia or breaking all ties with his home. Even though he’d served his time for the misdeed, the danger of blood revenge still existed,” Aspen says.

Still on guard

Pietro was present for the book launch in Bova.

“We were afraid for his safety when he came to the launch. He was glancing over his shoulders the whole time,” Aspen says. He points out that the public debate in Norway about blood and honour killings today are only related to Islam. But they are still part of Italian society.

Pietro’s brother, whom Pietro was punished for, was himself killed a few years later after joining the Mafia. The name of the Calabrian Mafia, N’Drangheta, is made up of the Greek words andrós (man) and agathós (good, brave), meaning “men of honour.”

The value of ethnographic material

Social anthropology

Social anthropology is the study of social and cultural aspects of human society. Central to anthropology are the concepts of society, culture and symbols. The subject is based largely on qualitative methodology, fieldwork, participatory observation and comparison. Anthropology explores both human variation and what all people have in common.

Aspen reflects on the value that ethnographic descriptions may have in retrospect. He thinks Brøgger’s study is an interesting example of how ethnographic material can benefit not only social anthropologists, but also the informants and their descendants.

The way Jan Brøgger carried out his research in Bova is the classical method of a social anthropologist, that is, to settle into a local community for a longer period, establish contact with the population and participate as closely as possible in their daily lives. In this way the anthropologist gains an intimate and detailed knowledge of everyday life and celebrations, values, cohesiveness and conflict. The method is called participatory observation.

“Many people in Bova are still impressed today with how the professor participated in their lives fifty years ago, and how he presented his observations in the book he wrote. This probably has a lot to do with the fact that good anthropological texts, like this one, help to understand society, without judging what’s good and what isn’t,” Aspen says.

“Maybe the book can contribute to allowing people to let go of the shame they felt about their position and origins, and perhaps even to replace it with pride,” he says.

The release of this book could help open the doors to discussing the more negative aspects of the Calabrian community – the Mafia’s continued presence, concepts of honour and blood revenge – and what kind of society people want in Calabria today. I know this was an important motivation for the two social anthropologists who undertook the Italian release,” Aspen adds.