How an intestinal bacterium from Bergen and a splinter from the Oseberg Ship became art

A playful artist duo invited scientists to take part in a collaboration, and they were more than willing to oblige. This is how an intestinal bacterium from Bergen and a 1200-year-old wooden splinter became public art.

A white, 3.5-metre-long light sculpture hangs from the ceiling of Hogsnes Health Centre in Tønsberg. Outside Bergen Light Rail’s Fyllingsdalen terminal, chains of bacteria cast in bronze twist upwards from the ground. Both are an unusual kind of public art.

The sculpture at the health centre is called ‘The Vessel’, and has been developed from a tiny wooden splinter taken from one of Norway’s national treasures, the Oseberg Ship. The artwork in Bergen is called ‘The Smallest Passenger’, and originates from a bacteria sample found on the Bergen Light Rail on 18 October 2019.

An extremely interdisciplinary collaboration

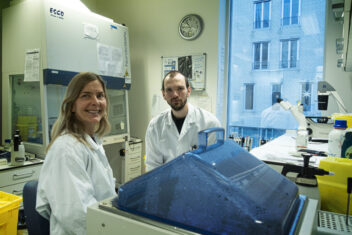

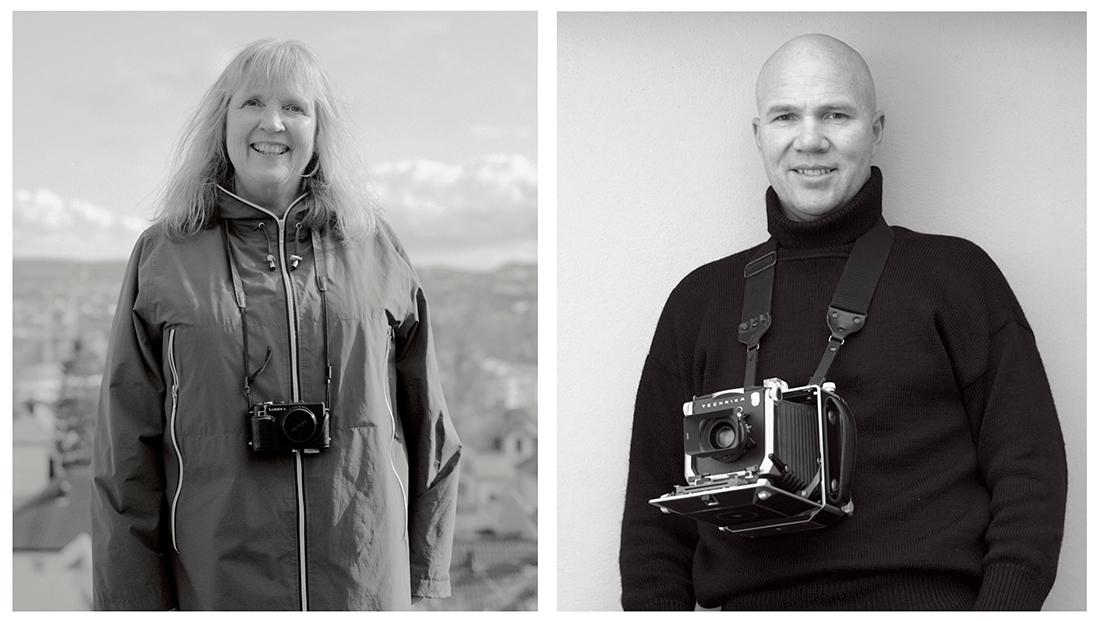

“This was all new to us. What makes it so rewarding and fun is that we see what we can achieve when people actually meet and talk to each other,” say Trude Helen Flo and Sindre Ullmann. Photo: Sølvi W. Normannsen

“Both pieces of publich art stem from an extremely interdisciplinary collaboration,” says Trude Helen Flo, Professor of Cell Biology at NTNU.

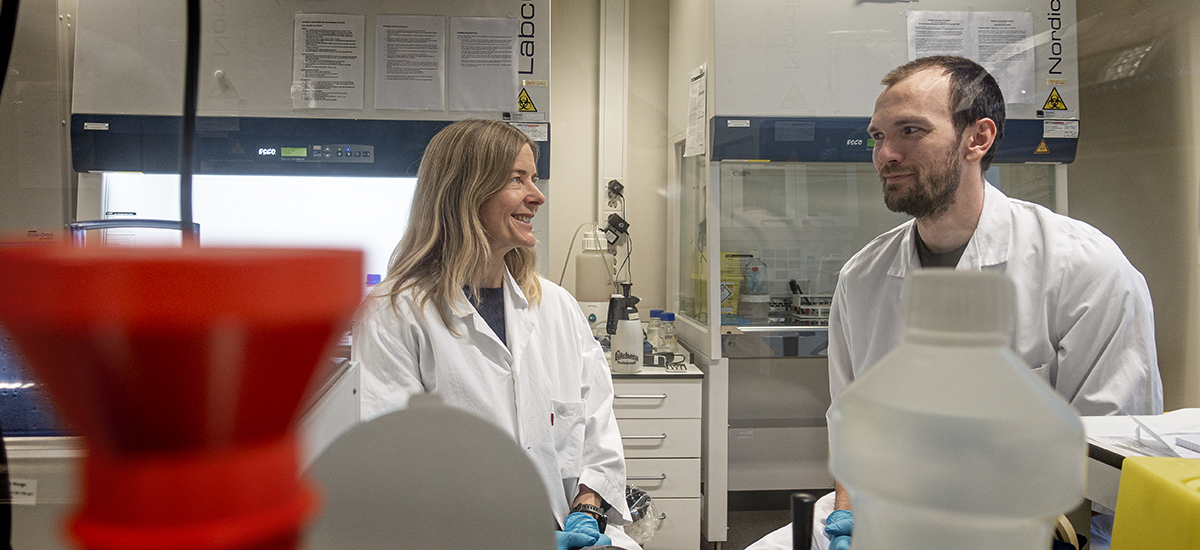

Together with her former PhD candidate, Sindre Ullmann, she has been involved in developing the public art sculptures together with the artist duo Beret Aksnes and Vegar Moen.

“It has been a lot of fun,” says Flo, who heads the Centre for Molecular Inflammation Research (CEMIR) at the Department of Clinical and Molecular Biology.

- You might also like: Pupils are making circular art for Oslo’s first “energy-plus” school

On display in Stockholm

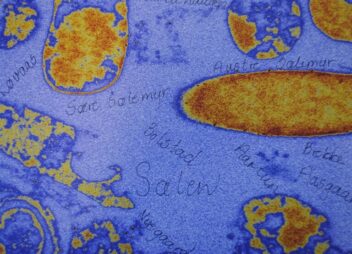

Intestinal bacteria from one of the seats on the train magnified thirty-three thousand times. Beret Aksnes and Vegar Moen. Photo: Vegar Moen

Parts of The Smallest Passenger have now travelled on to an exhibition in Stockholm. On Friday 9 February, The Spring Salon 2024 opens at Liljevalchs in Djurgården, which is widely regarded as Stockholm’s most beautiful exhibition space. Almost 5000 artists applied to participate in this annual exhibition, which is the Swedish equivalent of Norway’s Autumn Exhibition.

In the exhibition catalogue, great thanks are given to both the microbiologist at St. Olavs Hospital, NTNU Nanolab, Trude Helen Flo and her colleague Sindre Ullmann for their collaboration on the sculpture.

No shortcuts

The bacterium in Bergen has been magnified 33,000 times, while the wooden splinter that became a light sculpture was magnified 20,000 times.

“I was quite fascinated by the way the artists thought and worked. They could easily have found and used pictures and illustrations of an intestinal bacterium online, but that solution was never on the table. They insisted that the artworks should be based on the real thing,” says Trude Helen Flo.

Intestinal bacteria and tuberculosis

Trude Helen Flo conducts research on inflammatory responses. She is an expert in the interaction between cells in our innate immune system and bacteria such as mycobacteria and E.coli.

Mycobacteria cause diseases such as tuberculosis and leprosy, while E.coli occurs naturally in the colon and can cause us serious trouble if they manage to reach other parts of our body.

Began with The Big Challenge

The scientists and artists found each other in 2019 during NTNU’s science festival called The Big Challenge. NTNU Health and Trondheim Art Museum then invited them to take part in the Micro Challenge exhibition, where the theme was major global health challenges of our time.

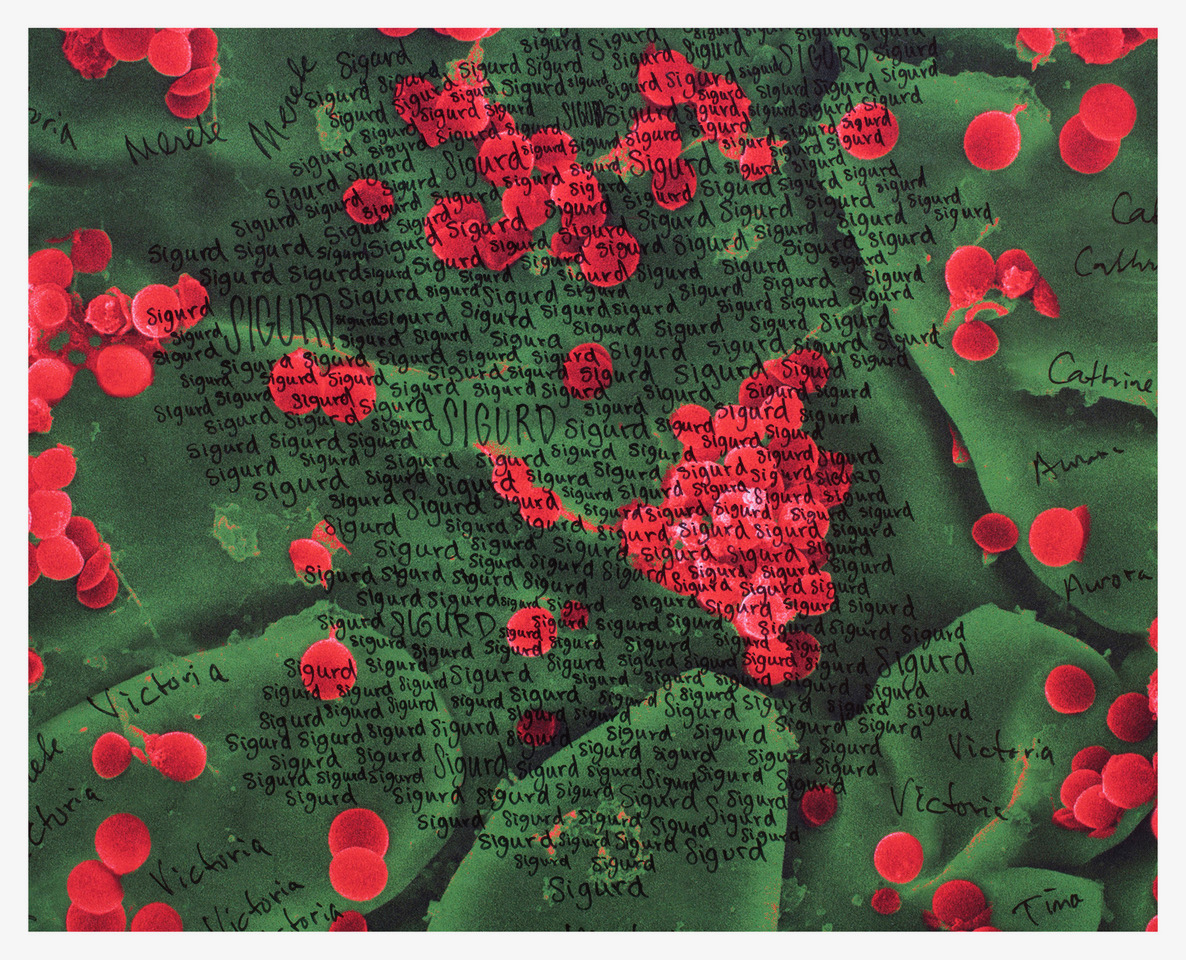

At the opening, Trude Helen Flo gave a talk about her research. The artwork that Aksnes and Moen exhibited was a tapestry of electron microscope images of multidrug-resistant bacteria from St. Olavs Hospital.

“We hand wrote the first names of all of Trondheim’s 192,000 inhabitants on the walls,” says Vegar Moen.

Imaging as a starting point

“It was really fascinating for me to hear that they used electron microscopy as a starting point, both for this artwork and for a commission up in Tromsø. Our worklso involves microscopic imaging, so what they were doing was not entirely foreign to us.”

The artwork in Tromsø is a rasterised steel belt (in Norwegian) measuring 3 x 21.5 meters that extends along the facade of the Medical and Health Sciences building at the University of Tromsø, The Arctic University of Norway. It is actually a super-magnified electron microscopic image of the brain of a fruit fly, a tiny insect that has been used in medical research for more than 100 years.

Fly brain. The artwork is made of perforated, mirror-polished steel and backlit using LED lighting. The electron microscope image has been magnified 2.5 million times. The fruit fly was caught, prepared and photographed by Senior Engineer Randi Olsen at the Advanced Microscopy Core Facility, IMB, UiT. Photo: Vegar Moen

Brainstorming

When they received the artwork commission from Bergen Light Rail, the artists contacted the scientists.

“Loads of ideas were thrown back and forth, and some had no connection with reality whatsoever. But even though they received some disappointing answers from us scientists that something wasn’t possible, they kept looking for new solutions,” says Sindre Ullmann.

He is a senior engineer at the Department of Clinical and Molecular Biology and has worked extensively with bionanotechnology and various electron microscopy techniques.

Collected bacteria

Artist duo. Beret Aksnes and Vegar Moen have collaborated on public art for public buildings since 2008. Photo: Vegar Moen/private

The Department of Medical Microbiology at St. Olavs Hospital was also eager to join the project. In autumn 2019, they sent equipment for collecting, transporting and storing bacterial samples to the artists.

On 18 October, Aksnes and Moen travelled on Bergen Light Rail collecting samples from seats, door handles and stop buttons. They also collected samples from the hands of young people at a disco in Fyllingsdalen.

The test tubes were returned to Trondheim and the samples cultivated. Finally, Sindre Ullmann received the small clumps of bacteria, which he then scanned at NTNU NanoLab.

Intestinal celebrity

Among the bacteria, they selected an old acquaintance: Enterococcus faecalis.

“It is a well-known intestinal bacterium that we would expect to find on public transport,” says Ullmann.

You could call it the smallest passenger – one of approximately a thousand billion living individuals travelling daily around our bodies, and all around us.

Sandblasted intestinal bacteria

To prepare the intestinal bacteria for use under the microscope, they first moulded it into epoxy glue.

Ullmann produces the images using an instrument that works like a combined sandblaster and microscope.

He practically digs a trench in a lump of plastic with the bacteria, and a beam of electrically charged atoms creates a cross-section of the sample. This acts as a transparent wall through which the bacteria can be imaged.

“You can then sandblast away a new layer for every photo taken. Finally, the pictures are stacked together into a three-dimensional image which we can put into software and reconstruct its appearance and behaviour,” says Ullmann.

Fell for its beauty

An unusual piece of public art: The Smallest Passenger, magnified 33,000 times – and measuring 2.5 x 3.1 metres. Photo: Vegar Moen

The artists say they fell for how beautiful the shape of the bacterium was. They had an exact 3D copy made, which was then used to make a mould for bronze casting.

“It really was a case of new technology teaming up with old craftsmanship,” says Aksnes.

The artists describe the collaboration with the NTNU scientists as ‘absolutely fantastic’.

“We felt comfortable asking any question whatsoever. The scientists were open, curious and tolerant, and they answered our questions and explained with great patience,” say the artists.

Taking the long road

Bacteria from the hands of local youths also adorn the roof of some of the carriages on Bergen Light Rail. The photos are tagged with old place names. Photo: Morten Wanvik/Vestland County Authority

“We have great respect for their expert knowledge, and we know that creativity, rigour and a lot of work are required to achieve research goals. It is really impressive,” says Beret Aksnes.

Professor Flo says she has never had the opportunity to observe the design process for a work of art so closely before.

“We had the privilege of seeing just how much the artists put into it. The importance of telling a whole story around what became the finished works. They really did take the long road,” she said.

Trude Helen Flo and Sindre Ullmann say the art project confirms that exciting and fun things can happen if you are willing to step outside your comfort zone. “If we had only been interested in ourselves and our own work, we would never have got involved with this,” says Ullmann. Photo: Sølvi W. Normannsen

From a minute splinter to a light sculpture

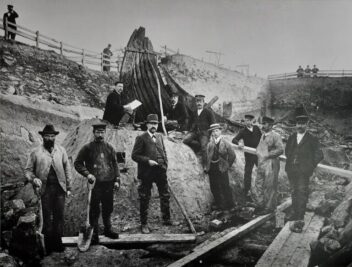

The Oseberg Ship, from the excavations in 1904. Photo: Olaf Væring, Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo / Wikimedia commons

After the intestinal bacteria project, the artists were commissioned to create a piece of art for the health centre in Tønsberg. It was in this part of Norway that the famous Oseberg Ship was discovered in a burial mound in 1903.

The ship was built around the year 820, and Moen and Aksnes wanted to make a historical connection.

Here, too, they didn’t take any shortcuts. After a lengthy process, they were finally allowed to use a tiny splinter of wood, only a few millimetres in size, from the original ship.

Authenticity is key

“It is hard to describe the feeling of getting the test tube containing a wooden splinter from the Oseberg Ship, and everyone could literally hold a piece of Norway’s national treasure in their hand,” says Aksnes.

The duo is always keen to find a concrete starting point when creating art for public spaces; a piece of reality that can surprise and engage. They always explore the place in question carefully, looking for stories and characteristics.

“Authentic origins often surpass what we might be able to imagine and have multiple layers and points of connection that add depth to the art. Therefore, finding a basis of authenticity is important,” says Aksnes.

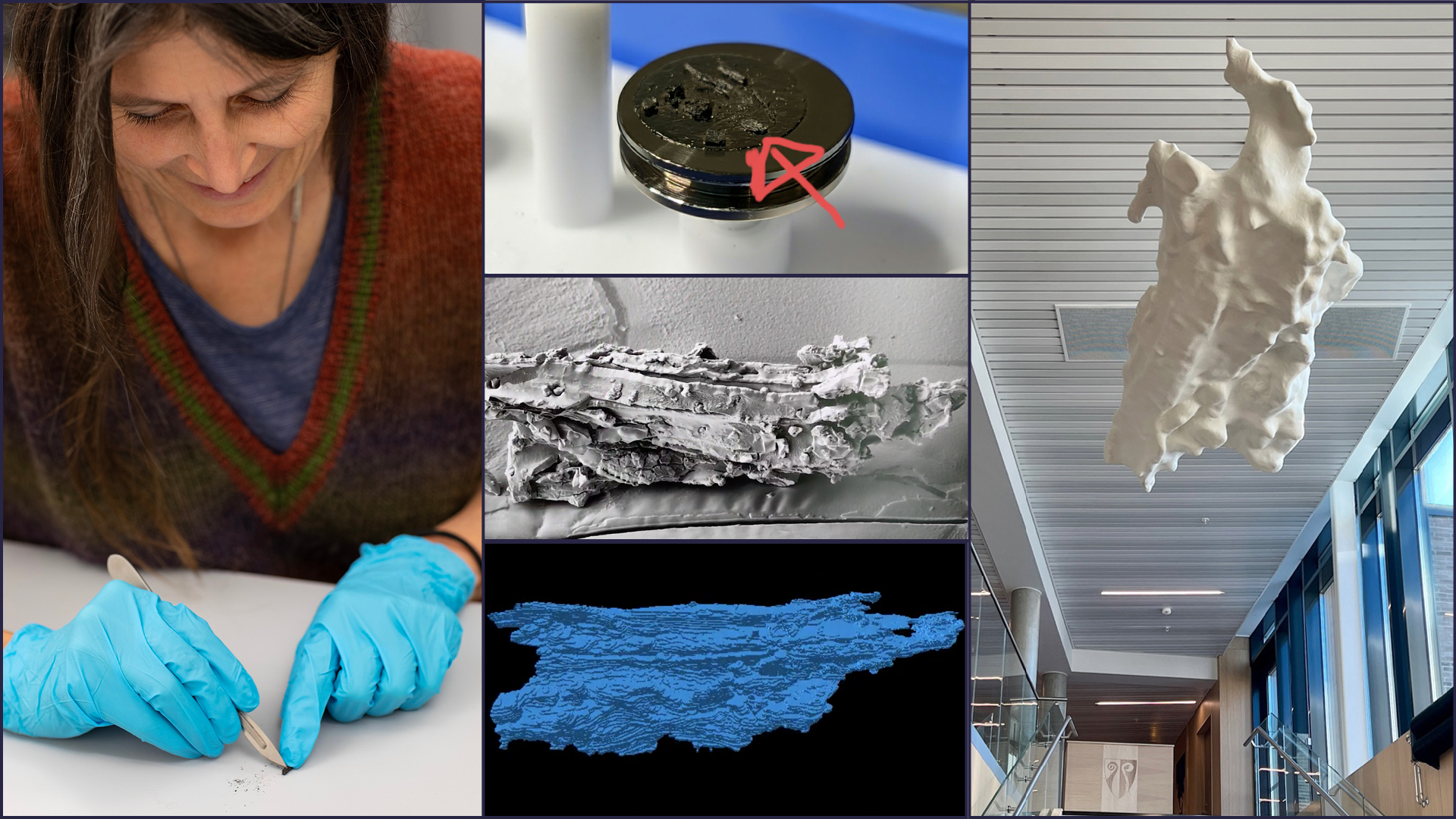

NTNU scientists removed the wooden splinter the arrow is pointing to in the picture on the left. In the middle: The splinter being prepared for electron microscopy – with imaging on the right. Imaging: Sindre Ullmann

A journey through time

Ullmann used the splinter from the Oseberg Ship to produce an image and created a 3D model.

The model became the starting point for a casting process in fibreglass, a material used in modern boat production. This is how the Vessel in its own way travelled through the centuries and ended up hanging from the ceiling of Hogsnes Health Centre.

Not possible without science

The artists work in a way that often requires collaboration with other disciplines, but they say that the collaboration with the NTNU projects has been especially close.

Susan Braovac, Curator at the Museum of Cultural History, sacrificed a tiny piece of the national treasure. The images in the middle show the wooden splinter, the electron microscope image and the digital 3D model that became the starting point for the casting process. The Vessel has a skeleton of steel and is cast in fibreglass, a material used in modern boat production. The surface is made of polyester, and the light sculpture measures 1.5 x 3.5 metres. Photo: Mårten Teigen KHM 2010, Sindre Ullmann, Vegar Moen.

“Without the help we received from the scientists and science, there would be no Vessel, The Smallest Passenger, or Fly Brain. We are not so interested in expressing our own feelings, but hope that the works of art can engage and awaken thoughts and feelings in people. We want to capture the accuracy and the possible truth found in science,” says Aksnes.