So what is “gand” sorcery – really?

Some people may have heard about the magical phenomenon of gand. When life seems to be against you or you’re plagued by one misfortune after another, you might jokingly say that you’ve been ‘ganda’ if you’re Norwegian. But what did gand really look like and why do we associate it with the Sami people?

Gand was originally understood as the soul or as spirit helpers that a person versed in sorcery could send out to obtain information from distant places or to harm others.

Historically, gand is linked to a magical system of thought of pre-Christian cultures that practised shamanism. The word is very old and, surprisingly, not Sami, but hails from the Proto-Germanic. The Old Norse form of the word is gandr.

Gand became the term that Christian priests and other scholars used to describe a type of magic that they attributed to the Sami people in the 1600s and 1700s.

- You might also like: First film in Southern Sami language wins prize

Evil projectile sorcery

Gand described a malicious projectile that a sorcerer could shoot at great speed and over long distances. Gandskudd, finnskudd and trollskudd are all words that describe the same phenomenon of shooting a projectile to cast a spell. These shots supposedly came from the north on the north wind, and were sent by peoples who lived remotely and had a dubious relationship with Christianity.

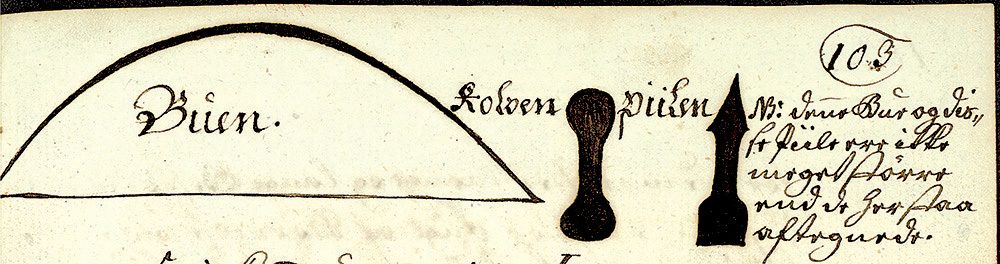

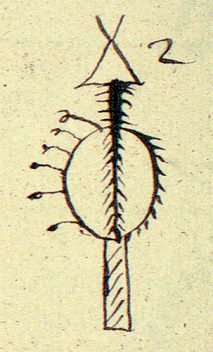

Olaus Magnus (1490-1557) was the first historian to imagine gand as arrows, with several missionaries subsequently making mention of them. The priest Johan Randulf (1686-1735) drew two variations of the magic Sami shot – one a sharp tip arrow and the other a blunt tip arrow, as well as the bow used to shoot them. The bow and arrows are no bigger than a finger. Randulf describes the drawing: “When the noaide [Sami shaman] wants to hurt or maim a human being that they are angry at, whether the enemy is near or distant, they use a bow made of reindeer horn and a blunt or sharp tip arrow …if they want to hurt him on the arm or legs … then they shoot the blunt tip at a picture of the body part they want to hit. But if they want to give him an open wound or continual pain between skin and flesh then they shoot with the sharp tip.” Illustration: XA Qv. 374, NTNU University Library

Shamans could also activate or connect with beings in the spiritual netherworld, who in turn could launch “elf-shots” and “earth-shots.” People believed that these kinds of projectiles were shot up from the ground.

Sarve Pedersen, a Sami who lived in Porsanger municipality in Finnmark county, was sentenced to death in 1634. He apparently was “taught by his godmother to take elf-shots, and then learned spellcasting and more.” The belief in elf-shots also goes a long way back in the Proto-Germanic mindset. You can find it in Old English, which was spoken in the Viking age, and it is mentioned in the 17th century witchcraft trials in Scotland.

- You might also like: Threatened language

Great torment and instant death

The different names for harmful sorcery projectiles all had in common that they usually struck suddenly and were accompanied by great pain and instant death. The shot had an explosive force and you could hear a bang when it hit. If a person succeeded in throwing the cursed shot into the flames, you could hear it hiss in the fire. This description could have something to do with the idea of fire as a sacred and cleansing element within Christianity.

What did gand look like?

In the known writings that refer to gand, it’s clear that the authors are talking about something physical and visible. The Swedish priest and Archbishop Olaus Magnus has provided us with one of the most famous depictions of the Nordic region in the 16th century in his book Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus (History of the Nordic Peoples), published in Rome in 1555. The work was quickly translated into several languages and gained great fame, and was long the most important source of knowledge about the Nordic region.

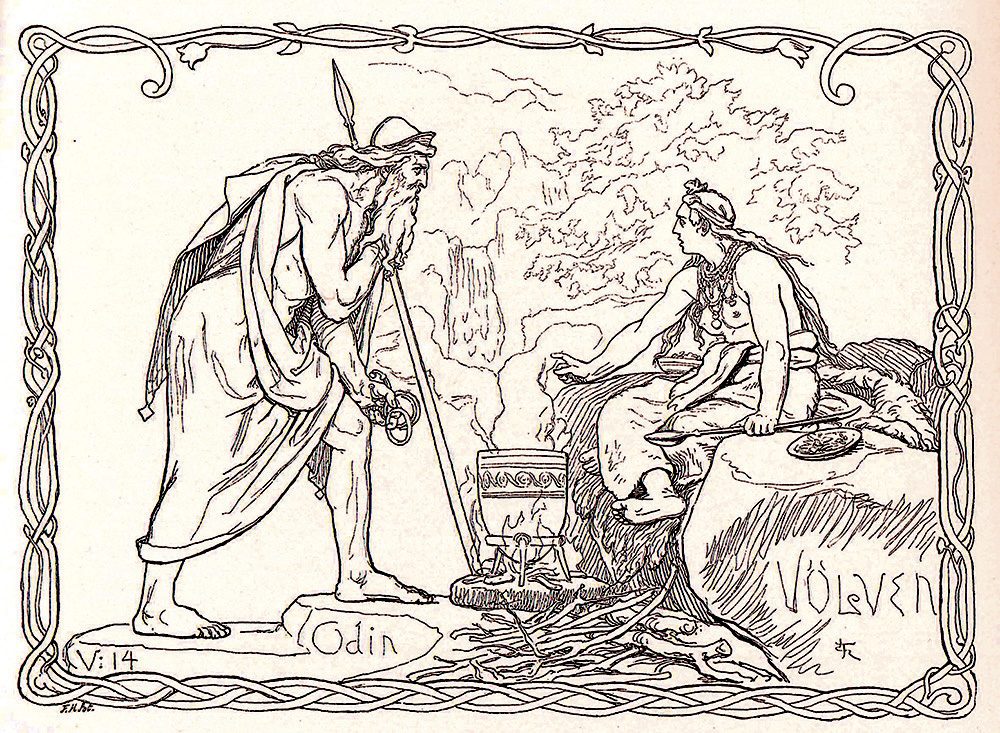

“Odin and Vølven” by Lorenz Frølich, 1895. In this pre-Christian Norse world image, Vølven was a respected and feared sorceress, a master of seid (the art of magic), divination, spells and magic song. The rituals involved shamanism, often using drums. Among the Sami, the noaide had a similar function, where joik and the use of shamanic drums were part of the magic repertoire. Illustration: NTNU University Library

Olaus Magnus based his sketches partly on his own study trips as far north as Tornedalen at the northern border of Sweden and Finland, and otherwise on conjecture and famous legends in historical writings. The author was able to frighten a European audience with his descriptions of both giants and monsters – and the terrible occult powers that existed among the northern peoples.

He mentioned Finns and Lapps as particularly able sorcerers, writing “there are sorcerers and spellcasters everywhere.”

- You might also like: Smokeless tents

Gand as lead arrows

Magnus wrote that the Sami could inflict people with different kinds of diseases, “and for this purpose, they craft small spell-spears, about the length of a finger, and shoot them as far as they want against those who are the object of their revenge.”

As far as I can tell, Olaus Magnus does not use the actual word gand in describing the northern art of sorcery, but he is clearly explaining a type of magic shot.

Peder Claussøn Friis

Peder Claussøn Friis (1545-1614) was the first person to describe the gand as horrid flies. He believed that the Sami kept the gand-flies in a leather bag. The little leather bag was an important part of the Sami costume, where the Sami kept small necessities. Photo: Dino Makridis, MiST – Sverresborg Museum

The southern Norwegian clergyman and historian Peder Claussøn Friis was the first to introduce gand as a distinctive Sami occult phenomenon in Norway’s written sources. His description of Norway and adjacent islands – Beskrivelse over Norge og omliggende Øer, written in 1613 and printed in 1632 – was also published in German and Latin and for a long time was the foremost source of Norwegian history and topography.

Friis, who himself barely travelled outside his own district, wrote a long and “enlightening” chapter about the Sami in northern Norway in his book . He most likely based his writing on perceptions that were prevalent at the time.

Gand-Finns

Friis relates that in Norway the Sami were called Gand-Finns because, regardless of whether they lived by the sea or in the mountains, they all cast magic spells called gand. According to Friis, the gand art of sorcery was hereditary, so that the next generation would be more proficient in practising the art than the previous one had been.

Coastal Sami even sent their children to be raised with relatives in the mountains, so that they would learn to cast spells. Gand was considered a kind of necessary self-defence. Anyone who couldn’t shoot spell-arrows risked being hit by another person’s gand curse.

According to Friis, this need to cast spells actually lived so deeply in the Sami that they only felt well if they sent out one of their spell-shots – directed either at people, animals, weather or wind – at least once a day. Some Sami even conducted blackmail with their magic art, he writes.

“As one Sami directed a gand-curse at a person, another Sami took money to remove it.” And, adds Friis, the world has never seen a worse sorcerer people than the Sami.

Gand as flies

Friis was the first to explain gand as being special flies that the Sami stored in a leather pouch called gand hiid. And when in a disagreement with another person or just bored, the Sami “sends his gand-flies out into the wind and lets them hit people, cattle or animals or wherever.”

Sometimes the Sami send their curses into the mountains and blow up big boulders, “and they shoot a curse at people and bewitch them just for fun.”

Johannes Schefferus

The next famous book that told about the gand as a Sami sorcery speciality was the pioneer volume Lapponia (1673). The author, Johannes Schefferus, was a German Uppsala professor and highly regarded scholar. He came to Sweden in 1648 by invitation of Queen Kristina.

Sweden commissioned Schefferus to write Lapponia following infamous rumours in Europe that the Swedes’ success in the Thirty Years’ War was due to help from Sami witchcraft. Schefferus’ mandate was to critically address some of the fanciful myths about the Sami people, but his work became one of the books that maintained the impression of the Sami as a people permeated with paganism and sorcery.

Lapponia was quickly translated from the Latin into a number of languages (English, German, French and Dutch), and was considered a standard work until the Norwegian missionary Knud Leem published Beskrivelse over Finmarkens lapper, a description of the Finnmark Sami, a hundred years later.

Gand as a little ball

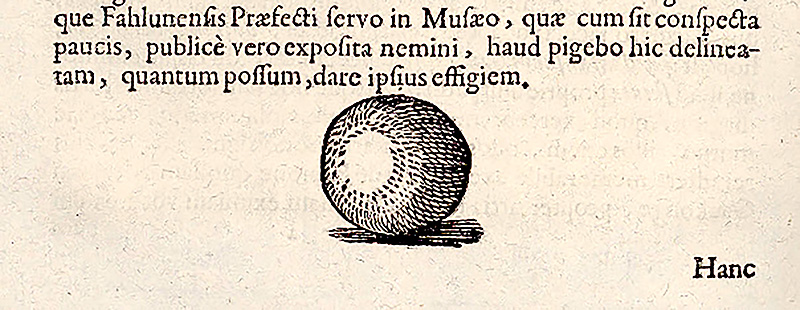

Schefferus described the gand as a little ball, which in Sweden was called gand-tyre, and depicted it in his book Lapponia. Illustration: NTNU University Library

In his chapter on “Sami sorcery,” Schefferus discusses the various aspects of this people’s knowledge of witchcraft. Schefferus was especially interested in gand curses. He didn’t think they were lead arrows, as Magnus believed, but rather gand-tyre. The word tyre is Swedish, not Sami, and is derived from the Finnish word tyrä, which means “sorcery ball”.

Schefferus describes gand-tyre as a round ball the size of a walnut and made of animal hair or moss. He had access to a gand-tyre in his museum and pictured it in his book.

Schefferus claims that the Sami could give the ball life through their art of sorcery, and would then sell it to someone who wanted to target his enemies. Gand balls flew fast and hit the first thing they encountered. Often a gand ball hit the wrong target, “of which we have many sad examples,” Schefferus adds.

The natural-science explanation for gand balls

A gand fly drawn on the back of a Sami shamanic drum from Rødøy in Helgeland. Poet and priest Petter Dass (1647-1707) spoke about gand as flies, which he called “Beelzebub’s flies” (devil’s flies). Johan Randulf (1686-1735) describes gand flies in the Nærøy Manuscript (1723): “Not all Sami have these flies but only the strongest and most learned shamans. When they rune [go into a trance] for them… a large flying bird the size of a goshawk or falcon appears. The bird spews out these gand flies from its beak, and some shake out of the bird’s feathers and wings. They are no doubt natural flies, but poisoned, that this Satan in his guise as a bird has brought down from some other place in the world, to the wicked service of the Sami. The Sami collects the flies and put them in a box, so he has them to send out as gand. Illustration: XA Qv. 23, NTNU University Library

The folklorist Nils Lid relates that in Norway the same hairball was called gandstein, or magic stone.

Sorcery occurred among both Sami and farmers

The works mentioned here were not just intellectual lectures, but in part also reading for literate peasants. The literature no doubt reinforced the impression of gand as a Sami magic phenomenon. In the witchcraft trials in the far north in the 1600s – at least where Sami were involved – accusations of gand were often a central part of the crime.

The Norwegian clergymen who were missionaries among the Sami in the 1700s were certainly well versed in the learned works that existed about the Sami people. The priests’ writings about the paganism and heresies of the Sami advanced their view of the gand as a Sami sorcery speciality. The priests describe gand as evil flies, balls or arrows, or a combination of these. Even today, we still think about gand as something the Sami were skilled in.

Likewise, traditions from the original Old Norse understanding of gand must also have lived on in peoples’ beliefs. In some cases, Norwegians and other isolated or marginalized peoples, such as beggars and gypsies, were known to have sorcery skills.

In some witchcraft trials in Sunnmøre, Norwegian sorcerers were specifically accused of gand, and one of them was also known to have a relationship with the gypsies.

For more information (in Norwegian):

- Alm, Ellen 2016. Hekseprosesser på Sunnmøre. I Årbok for Sunnmøre.

- Fritzner, Johan 1877. Lappernes hedenskap og trolddomskunst sammenholdt med andre folks, især nordmændernes, tro og overtro. I Historisk tidsskrift, bd. 4.

- Hagen, Rune Blix 2015. Ved porten til helvete. Fra s. 78. Cappelen Damm.

- Heide, Eldar 2006. Gand, seid og åndevind. Dr.art.-avhandling, Bergen.

- Lid, Nils 1950. Trolldom. Nordiske studiar. Cammermeyers boghandel.

- Willumsen, Liv Helene 2013. Dømt til ild og bål. S. 104, 215–216. Orkana akademisk.

This article previously appeared in the journal Spor, published by the NTNU University Museum.