When the Chinese giant awakes

When China sets its sights on a goal, the country can change at a blindingly rapid pace. Now the country is focused on innovation and technological innovations, with renewable energy at the forefront.

How well China succeeds in transitioning to renewable energy will be crucial for China as well as for the world – both in terms of the impact of pollution from today’s coal-fired power plants and in terms of developing green technology.

This vast country with its enormous population has shown us before that it is capable of bringing about major revolutions in a short period of time.

But we’ll come back to that.

Innovated in China

Innovation, education, research, technological solutions and economic development are now on the agenda of the country that is home to one-fifth of the world’s population. China is making a shift from being characterized as a “copycat” that produced cheap replicas of Western technology, to becoming a technology innovator.

“Made in China” has become “Innovated in China.”

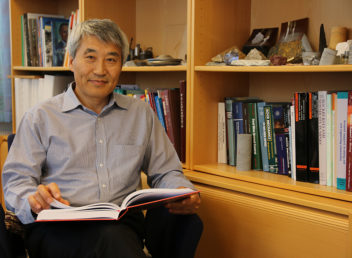

“In recent years, development has been exploding, and the country’s self-confidence has grown with it. The Chinese people work hard and we expect China will be creating big things very soon,” says Charlie Chunlin Li.

Li is a professor of rock mechanics and mining sciences at NTNU and has followed major education and research developments in China, both as an insider and from abroad.

High-tech laboratories

China invests big sums in research infrastructures and high-tech laboratories.

“The strategy of investing heavily in education, research and technology development started about thirty years ago. Initially, not much money was involved, but now big amounts are awarded. Money is no problem,” he says.

“And in addition to investments at the government level, the private sector and provinces and cities are also investing,” says Li.

Relaxing at the Yu Garden market in Shanghai, where the traditional and modern China live side by side. Photo:Idun Haugan/NTNU

NTNU Research and Innovation Center in China

The city of Nanjing and Jiangsu Province’s commitment to the NTNU Research and Innovation Center are an example of these kinds of regional investments.

This past spring NTNU entered into a Memory of Understanding (MoU) agreement with the city and provincial leadership. Several universities and businesses are party to the agreement.

An MoU is basically an agreement of intent to cooperate, but Chinese partners are already prepared to invest more than NOK 100 million in the initial phase of the collaboration.

The goal of the agreement is to develop products and commercialize research and innovation.

How this will actually happen in practice, including the issue of patents, remains an open question.

Silicon Valley of the East

Nanjing is China’s leading city for innovation and technology development and is located in the province of Jiangsu, China’s fastest growing province economically.

NTNU’s Research and Innovation Center will be built in the middle of a high-tech park surrounded by 50 businesses, like a piece of Silicon Valley transplanted to the Orient. A number of high-tech parks have been established in China in the past 20 years.

Article continues below photo.

Officials from NTNU and Nanjing sign an MoU on the NTNU Research and Innovation Center. Photo: Idun Haugan/NTNU

China is vigorously pursuing research and education collaboratives with other countries. The Norwegian delegation from NTNU’s Ministry of Education and Research that visited Chinese universities in April 2018 has put this collaboration on the national agenda.

NTNU is one of the Norwegian universities that has already established cooperative programmes, and several new research projects and educational exchanges are under development.

Huge home market

NTNU’s partner universities are located primarily in Beijing, Shanghai and the former Chinese capital of Nanjing. People in these three megacities live tightly packed together, in, up, and across across the cities’ enormous expanses. It takes hours to navigate from one end of the city to the other.

Cities that were known for their masses of people on bicycles a few decades ago now have streetscapes dense with car traffic. People wear pollution masks to protect themselves from the exhaust and the pollution from the coal-fired power stations that still dominate, despite the country’s major commitment to renewable energy.

With its 1.4 billion residents and a correspondingly huge need for renewable energy, China is a huge market on its both for itself and for the world.

Article continues below photo.

China’s megacities are growing in area but also into the sky. The photo shows the Shanghai skyline. Photo: Idun Haugan/NTNU

Renewables on the advance

Asgeir Sørensen, director of NTNU AMOS, has a lot of contact with China through research collaboration in marine technology and student and PhD candidate exchanges.

He believes it won’t be long before major changes occur in China on the energy front.

“I predict that in ten years China will be supplying renewable energy instead of coal power and that they’ll become an engine in developing renewable energy worldwide,” he said. “My prediction is that it will be just a short time before we see China transition completely to renewable energy. Pollution is poisoning the big cities. Renewables are the way forward.”

“And in China, big changes happen fast,” he adds. “When the political leadership decides on something, the cogs begin turning and the follow-through on decisions is thorough. Throughout history, China has shown that they are able to make major changes in a short amount of time.”

Sørensen compares China’s pollution circumstances with the situation in Japan and Germany after the World War II.

“Germany and Japan had been intensively bombed and had to start from scratch to rebuild their countries. They had the ability and the will to do it. Eventually, their efforts gave these countries a significant competitive edge in new technologies and production,” he said.

“China isn’t very far from an emergency situation in terms of pollution, and it has to take action to create a new situation. And the Chinese have the ability and the will.

“China is good at commercializing what they do, and the transition to green energy that is underway is not a threat or a problem, but a huge business opportunity,” says Sørensen.

Article continues below photo.

China’s Share Bike programme has brought bikes back to city streets —but pollution from automobiles remains an omnipresent problem. Photo: Idun Haugan/NTNU

Why should Norway cooperate with China?

Johan E. Hustad is the director of NTNU Energy, one of NTNU’s strategic research areas. He has extensive experience with Chinese universities, mainly in Shanghai. NTNU’s collaborative efforts are now expanding and being formalized, focusing on offshore wind power, heat pump technology, energy systems in buildings, smart grids and hydropower.

“Eight to ten years ago, for example, only a few Chinese companies were working on solar cells. Now they’re at the forefront worldwide in solar cell production,” says Hustad.

“We can learn a lot from cooperating with China, such as how they think technically. We see things in different ways, and cooperation expands our perspective,” he says. “What I observe in China is that the process from research to implementing research results moves fast. Eight to ten years ago, for example, only a few Chinese companies were working on solar cells. Now they’re at the forefront worldwide in solar cell production.”

NTNU’s Professor Li, who is from China, says, “It’s quite easy to raise money in China to commercialize research. Norway doesn’t have much competition between Norwegian investors, whereas in China investors are eager to commercialize research and develop products. In Norway, commercialization processes are a lot slower than in China.”

He has experience with this through his invention of the D-Bolt, a flexible bolt used in mining to keep mountain masses in place when tensions occur in the rock. The D-Bolt is now in production and helps secure mines and tunnels worldwide.

But it took time to get the device into the market. It would probably have happened much faster in China.

“One aspect that needs to be clarified in relation to how the Chinese commercialize innovations is how they handle patents and ownership. With the D-Bolt, NTNU Technology Transfer (TTO) was responsible for this process and they have solid expertise in this field,” says Li.

This past summer, Li gathered 145 participants from 18 countries for a major international conference in Trondheim, RocDyn-3 (the 3rd International Conference on Rock Dynamics and Applications), including 60 participants from China.

Research in rock mechanics (tunnels, rock chambers) is one of the several collaborative research projects between NTNU and China.

Leading the world in sun and wind power

Over the space of just a few years, China has become the world leader in solar cells and wind power. Energy needs – and the market – are immense, especially on China’s east coast, where the country’s largest cities gobble up huge amounts of electricity.

“China started getting really interested in wind power in 2002, and since 2006 they’ve developed and adopted the technology very fast. They’ve been the world leaders since 2012. China is the world leader in everything having to do with renewable energy,” says Marius Korsnes, a postdoctoral fellow at NTNU.

He is studying the role of “prosumers” and new forms of energy use in low-energy buildings and areas. Prosumers are energy consumers who also produce energy. Korsnes is comparing prosumers in urban areas of Norway and China.

Norway is interested in collaborating on onshore power and offshore wind power.

“In Norway, Statoil and Hydro are way ahead in terms of wind power technology, including offshore wind power. Norway has a big advantage in being able to transfer knowledge from the oil industry. Hydro, which is currently setting up large offshore wind farms off of the Scottish coast, sees a large international market – especially in China,” says Hustad.

In the case of solar power, solar cell factories benefit from state subsidies, and China has hijacked a big part of the world market. In recent years, the price of solar panels has fallen a lot.

Huge plants have been built in the Gobi Desert in the north towards Mongolia and in Gansu province in the northwest. China has a target of covering ten per cent of the country’s energy needs with solar energy by 2030.

One challenge is that the power grid is not dimensioned to cope with and use inconsistent production from solar power, wind turbines and other renewable energy sources.

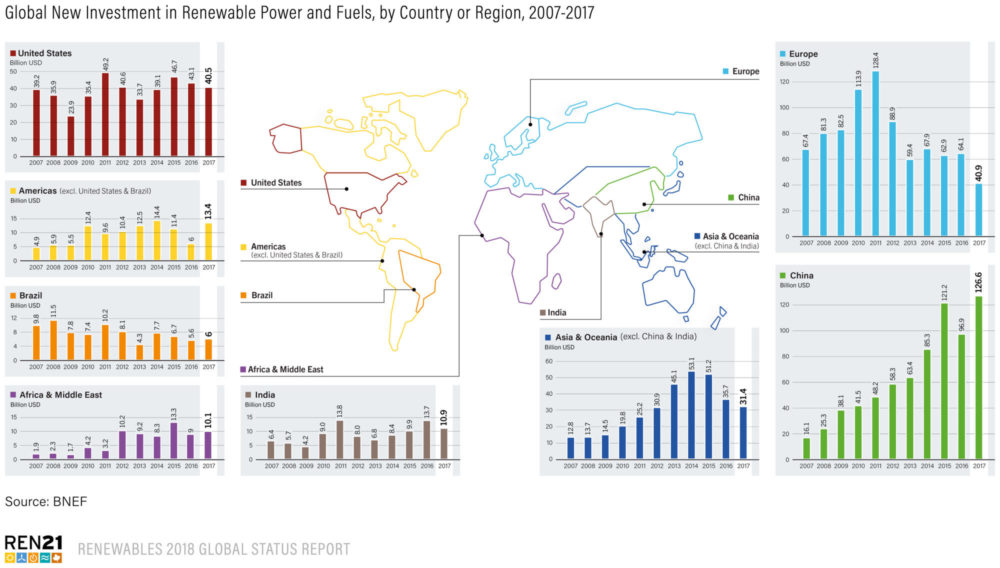

Article continues below infographic.

Overview of investements in renewable for different countries from 2007-2017. Source: Renewable Energy Policy Network. More infographics: https://www.ren21.net/status-of-renewables/global-status-report/

China yesterday, today and tomorrow

Throughout history, China has shown that it is capable of enduring major upheavals over a short period. But not all of them have been for the good.

Until 1911, China was an empire that had significant influence on the world for hundreds of years. Chinese technological supremacy led to inventions like the compass, the art of printing, gunpowder, mechanical watches, toilet paper, writing paper, banknotes – all innovations that became important to the West.

In the 1400s, during the Ming Dynasty, the Chinese explored the world and made great journeys of discovery with their huge fleet, long before Christopher Columbus sent off to sail the ocean blue and stumble over North America.

But then the country closed its doors, as it had done for long periods before.

Opium for the people

With its large population, vast geographical expanse and huge internal markets, the great power in the East was an inward-looking country for long periods.

The outside world was interested in exclusive products such as silk, porcelain, tea and spices from China, which were very attractive commodities. Especially in Europe demand was high. But trade suffered from China’s lack of interest in foreign products.

In their search for merchandise to trade, the British found opium.

Along with other Western superpowers, they essentially pushed their way into the Chinese market with opium as the commodity. In short order, opium dens established themselves in the big cities, and millions of Chinese became addicted.

The Chinese empire tried to end the trade, but it was so highly profitable that Britain went to war to retain its opium exports. The Opium Wars were the first in a series of events in the 19th century that opened China to foreign trade and Western influence by force.

Mao and communism

Mao Zedong established the People’s Republic of China in 1949, changing the nation irrevocably. Photo: NTB Scanpix

The enormous class differences in China led to constant uprisings in the late 19th century, contributing to the fall of the empire in 1911. Three decades of power struggles between the Communists and the Chinese People’s Party, Kuomintang, ensued.

Mao Zedong won the power struggle and established his major socialist project that radically changed China .

Chinese socialism included benefits such as free education and equalization of class differences. Work for all was a mantra in Mao’s China. And there was indeed work for everyone, but the quality was not always the best. The country saw a rise in prices for cheap products, which were often copies of products developed in other countries.

Mao’s regime also controlled people’s lives through major indoctrination, strict censorship and extreme surveillance.

The Communist Party is present in most parts of the social structure and in universities to this day. Every university has a leader appointed by the Party – i.e. the country’s leadership – in addition to an academic leader.

Charlie Li in Mao’s China

Charlie Li was born in a small town with 6000 inhabitants in Shandong province in eastern China in 1957. He grew up in Mao’s China and experienced the massive changes that occurred in his country.

The Great Leap Forward that took place from 1958 to 1962 was set in motion to lift China’s economy and show the West that China was an industrial power. The goal was to mobilize the masses and transform China into an economic and military superpower.

Mao was intent on China becoming a steel-producing nation to demonstrate the country’s development and industrialism.

He ordered all metal to be collected, including kitchen equipment like woks. The metal was melted to reach the unrealistic goals that were set.

Large segments of the population were shifted from agricultural production to the steel industry. This, along with the totally misguided changes in agriculture that were imposed, led to catastrophic famine in some parts of the country.

Li remembers poor conditions in his childhood and that food was not plentiful.

Criticism strikes back

Most people – both women and men – dressed the same, in simple blue cotton uniform-like clothing called “Mao suits.”

In the years 1966 to 1968, while Li was still in primary school, he recalls a lot of chaos.

He describes how the teachers encouraged the children to voice criticism. To expose potential regime critics, Mao had urged everyone to come with criticism, directed both at others and at themselves. However, this could bring unexpectedly harsh retaliation.

“We were young and we didn’t understand that much. But it was a scary time. The brother of one of my classmates, who was only six years old, crossed out the name of Mao on a wall poster. At that time, an X on a name brought the death sentence. He didn’t understand what he did and was simply copying what he’d seen on other wall posters. This boy was subsequently bullied and carefully watched at school,” Li said.

Another event involved a girl who threw a badge with Mao’s picture on it into the toilet. The father of the girl, who had been encouraged to confess, told the story to his Party comrades in idealistic and good faith.

The father ended up being thrown into prison.

Required to work on a farm or factory

The upheaval in the country meant that schooling was repeatedly interrupted. But Charlie Li had a thirst for learning and was able to continue his education into high school.

Then the education system came to a virtual halt.

“During this period, it wasn’t possible to go directly from upper secondary school to university. You had to work three years in agriculture, factory work or in the military before you could be considered for higher education,” Li says.

He worked as a farmer, then as a mechanic at a factory, and studied on his own. The libraries contained only political propaganda literature, so he continued to read upper secondary school textbooks.Article continues below photo.

While the Cultural Revolution was at its most intense between 1966 and 1969, the universities did not accept any new students; political work and mobilization were on the agenda instead.

Between 1970 and 1976, the universities accepted some “worker-peasant-soldier students” who were recommended based on their loyalty to the Party, after they had contributed their three years of production work.

But with the new times, this admissions method was eventually rejected, and national entrance tests were reinstated.

“The first National College Entrance Examination after the Cultural Revolution took place in the winter of 1977. I was admitted to university after taking this test,” Li says.

Charlie Li was the only person from his town who started university that year, and he was among the 0.2 per cent who at that time embarked on higher education.

Today, 43 per cent – or 170 million – young Chinese pursue higher education.

A new era

Deng Xiaoping reformed China’s education system.

He succeeded Mao and made his mark as the great modern reformer. He started opening China to the outside world and implemented private enterprise reforms. No longer would everything be state owned.

“Deng Xiaoping decided that it was time to invest in education. This was a great period – the universities re-opened and people were given the opportunity to pursue their education. He embarked upon economic reforms and created hope and optimism. Xiaoping is a big figure in Chinese history. He was as strong as Mao, but whereas Mao thought power, Deng thought economy,” says Li.

“Making room for self-initiative motivates people and gives them the opportunity to create better conditions for themselves and their families. It’s like a motor in society,” he says.

Li’s advisor at university had formed a collaborative relationship with Luleå University of Technology in Sweden, where he had taken his doctorate. Li was groomed to do the same; he received a scholarship and took his doctorate in rock mechanics in Luleå.

Since then he has been working in Scandinavia. He started in Sweden with research and engineering related to the Swedish mining industry, and since 2004 has been employed at NTNU.

“I fit quite well into Scandinavian culture. The concept of equality in Scandinavian society suits me well,” he said.

Sources:

- “Wild Swans. Three daughters of China”, by Jung Chang.

- “China — a journey on the river of life”, by Torbjørn Færøvik (in Norwegian)