How you can reduce your pain

Are you bothered by persistent pain? Here’s a pain physician’s advice on how to change your perceptions of pain and get a grip on it.

Some people suffer from chronic pain. Others have pain that eventually goes away. Whether short-lasting or chronic, pain can be aggravated by lack of sleep, being under or overweight and smoking, as well as inactivity, anxiety and stress

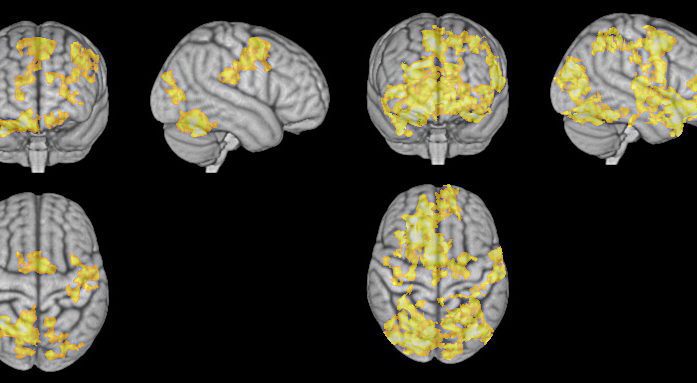

Pain as a separate field of research only took off in the 1960s. Previously it had been assumed that pain had to have a specific origin. Since then, the understanding is that pain can exist on its own, without necessarily being caused by injury or illness.

“A lot goes on in the brain and nervous system to regulate pain. It doesn’t have to have a known cause,” says Egil Fors, a general practitioner and psychiatrist who works at NTNU’s Department of Public Health and Nursing on a daily basis.

He distinguishes between acute and chronic pain. Acute pain can take numerous forms, but the common characteristic is that the pain goes away after a while.

Imagine a marathon runner or your favourite top athlete coming into the home stretch of a race.

Petter Northug, a former elite Norwegian skier, described the feeling this way in his biography: “First I feel the pain in my legs. Then in my chest. But I have to push on. Until my temples begin to pound, until my gaze narrows, and the alarm goes off through my whole body. That’s when I make my move.”

It’s normal for pain to accompany intense physical effort. To push through the pain, there are techniques you can use to distance yourself from it.

Mindfulness training

“We know that a lot of marathon runners start counting from one to 100 towards the end of a race, and focus only on that. Skiers can almost completely detach from their pain by thinking about proper technique and focusing on not feeling it,” says Fors.

You can train yourself to block out unnecessary impressions with the help of mindfulness training.

“If you’re on a bus, for example, you can start listening to only one particular sound. Once you can do that, you may eventually be able to transfer the technique to another situation, like blocking out pain,” Fors says.

Mindfulness techniques can also be useful in pain situations.

Fors says mindfulness involves “being present here and now, and not dwelling on things in the past or on what might happen. For example, if you have a stomachache, you might start imagining that it’s cancer. Then you get scared and start imagining all kinds of things. Mindfulness techniques help you focus just on the present, and what’s happening right now.”

Make a plan

Self-hypnosis and guided imagery are other techniques you can use to manage acute pain.

Self-hypnosis requires first getting into a relaxed state and then into a kind of trance where you can numb the pain. This is particularly helpful in cases of severe nerve pain, such as after accidents.

Fantasy travel can be a form of relaxation using guided imagery where you envisage a problem or condition that you want to fix or attain. The next step is to envision a plan and visualize a way to solve it inwardly, in a safe environment and without pain.

Before every race, Norwegian World Cup alpine ski racers Kjetil Jansrud and Aksel Lund Svindal visualize and know every millimetre of the course in their minds. You can do apply this technique with painful procedures by having a plan in advance so you don’t jump into situations completely unprepared,” says Fors.

Movement is important

Dealing with prolonged or chronic pain often requires getting used to living with it.

Inactivity, in addition to poor sleep, tends to intensify chronic pain. Fors continually encounters patients with chronic pain who are afraid to move.

Back patients are often afraid that walking will make them feel worse. And patients with neck pain may fear becoming paralysed if they move their necks. In the worst cases, patients may refuse to go out at all and end up in a downward spiral, where they just sit at home and worry as the pain continues to worsen.

“The idea that you shouldn’t move is a myth. On the contrary, moving is key. But it’s important to approach it gradually. If you have back pain and are told to walk but overextend yourself on a slightly longer walk, you may hurry home and not dare to go out anymore. It’s better to start with a short walk and have a good experience, so that the good feeling is what remains and you keep getting out,” says Fors.

Accept the pain

Many of Fors’ patients have a hard time understanding that their pain is permanent.

“We tend to think that everything can be fixed, but that’s not always true,” he says. “With an injury or a terminal disease that you won’t rebound from, it won’t get better from banging your head against the wall or searching high and low for a cure that doesn’t exist. Instead, we can identify the values we still have in life. For example, is it more important for you to isolate yourself with pain than to go to art exhibitions, or be with your grandchildren or good friends?”

Many of the techniques Fors uses in treatment are about getting to the bottom of the pain and challenging thought patterns.

“If you think that your pain limits you, then it will,” he says.

But if you choose to accept the pain and instead see what’s worthwhile in life, you won’t put your life on hold. If you can accept that the pain is there, it often feels easier,” says Fors.

Egil Fors has written the book Hva er smerte? (What is pain?). He has also served as co-editor of the anthology Smertepsykologi, published in 2017, and published scientific articles on pain.