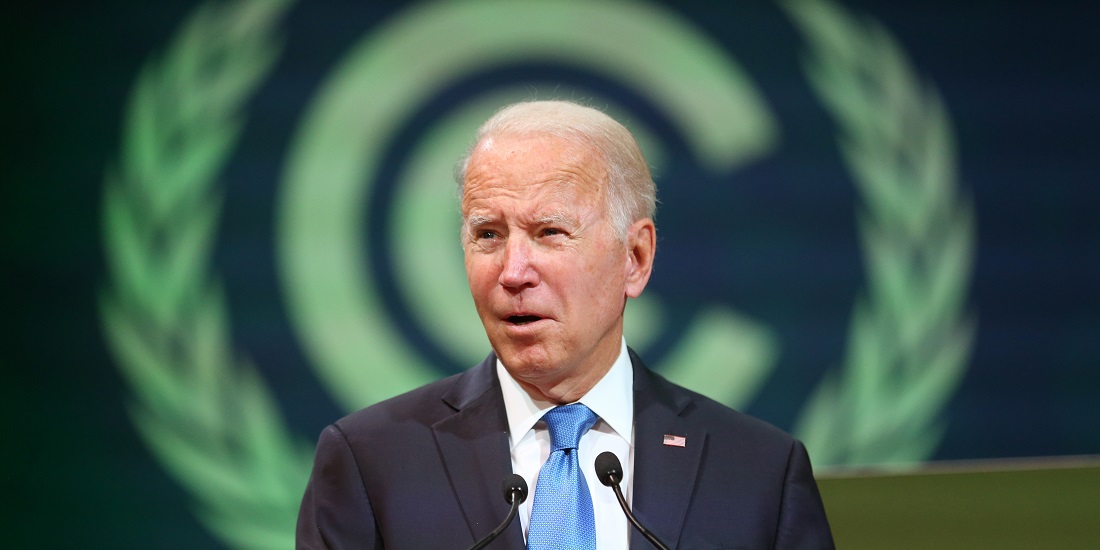

Another climate summit that changes almost nothing – again?

World leaders have gathered in Glasgow to discuss climate change. But the most likely outcome is that actions won’t extend beyond the talk.

The UN’s 26th climate conference in Glasgow comes right after a report published by the International Climate Panel. The report prompted politicians, the media and many others to address the issue using clichés and hyperbole. Now is the time to move from words to action! Again.

More of the same is the most likely outcome.

We’ve heard this all before. How likely is it, really, that we’ll see changes in practice this time?

“More of the same is the most likely outcome. The USA is back, but of course no one has any idea for how long,” says Espen Moe, a professor at the Department of Sociology and Political Science at NTNU.

The three largest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions are China, the United States and India, so that these countries have to be included for there to be any real changes. But China is not offering up any new climate promises this time, and India isn’t aiming to achieve zero emissions until 2070. That’s a long time in this context. So what about the United States?

“The intentions on the American side are at least greater than they were before, not that any of what’s happening in Glasgow is likely to be ratified by the US Senate,” says Moe.

Do you think changes will happen when 200 countries meet? Unlikely. Illustration photo: Shutterstock, NTB

Real change has to take place locally

Climate policy is primarily created at the local level, not in large meetings between 200 countries, Moe says.

This year’s parliamentary election in Norway was supposed to be the big climate election, but it fizzled out in the oil sands too.

Matto Mildenberger is an assistant professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara and is of the same opinion as Moe. He recently criticized Norway’s lack of political climate measures and capacity to implement them in an article in the Norwegian journal Energi og Klima (Energy and Climate).

This year’s parliamentary election in Norway was supposed to be the big climate election in, but it fizzled out in the oil sands too.

“Climate wasn’t really in issue in the election in Norway, which only moderately surprises me,” says Moe. “Instead we ended up with trench warfare for or against Norwegian oil production rather than discussing the politically difficult topic of domestic power production.”

Climate issue big only where people have enough

When the political parties that embrace climate as an issue can’t even manage to succeed in Norway, it doesn’t exactly offer much hope for success in countries with significantly poorer economies.

“The climate issue is big in a fair number of countries, but especially in countries with good living situations,” Moe says.

Moreover, politicians’ interest in economic growth tends to increase whenever there is an economic crisis. If your population is primarily struggling to provide food and clothing for the kids, or wants a refrigerator, a new TV and a life like people have in wealthier parts of the world, there’s no guarantee that people will care as much about climate change.

The UN Climate Panel regards nuclear power as part of the solution. Not everyone agrees. This photo is from Antwerp in Belgium. Photo: Shutterstock, NTB

Counter-reaction to climate policy

Countries are more polarized than they used to be. We see this polarization not only between, but also within, countries.

If you belong to the part of the population that defines themselves in opposition to society’s elites, you’re probably more sceptical of climate policy now than you were ten years ago.

“The climate issue has higher status today than ten years ago in the political establishments, but the polarization is also greater than it used to be. For example, we had an uproar over oil in Norway,” says the professor.

Moe believes that if you belong to the part of the population that defines themselves in opposition to society’s elites, you’re probably more sceptical of climate policy now than you were ten years ago.

“We’re finally getting to the point where the policy consequences are starting to become concrete and tangible, but it turns out that lots of people aren’t interested in sacrificing anything – which may not be that surprising, actually,” says Moe.

This doesn’t offer much hope to people who believe the climate fight comes first.

“The societal changes that are needed are so extensive that without broad legitimacy among the people, we have no chance. This applies to a rich country like Norway, which hardly has any social and economic problems beyond what politicians try to convince people of in an election campaign,” says Moe.

- You might also like: Map shows carbon dioxide emissions for more than 100,000 European cities

Unpopular climate measures

Several climate measures are hugely unpopular in parts of the population. In Norway, wind power is controversial and hotly debated, and the criticism so far has been directed primarily at land-based development. But offshore wind is not without its problems either.

Substantially building out nuclear power is one of the climate measures favoured by the UN Climate Panel.

Although another measure might quickly become even more controversial in Norway as well.

Substantially building out nuclear power is one of the climate measures favoured by the UN Climate Panel. Along with some other countries, Germany has strongly opposed this tactic. The country is instead shutting down all its nuclear power plants.

According to Moe, phasing out nuclear power before it’s necessary is inappropriate. “Germany shot itself in the foot there, although it’s more complicated than some people think,” he says.

“To believe that some countries will massively reduce their energy consumption is completely unrealistic.”

Renewables are only realistic solution

With the technologies available to us today, there is no way around renewables, Moe says.

“To believe that some countries will massively reduce their energy consumption is completely unrealistic,” says Moe.

The politically realistic solutions are renewable energy and carbon storage.

We might see some limited exceptions in countries with a demographic decline, such as in Germany and Japan, where the population is shrinking. But even there we’re not talking about a big decline in energy consumption.

“The politically realistic solutions are renewable energy and carbon storage,” Moe says. “But I suspect that different types of carbon capture directly from the atmosphere will also be highly relevant in a few decades. This is because they’re interesting technologies and because I suspect that in a couple of decades we won’t have developed renewable energy fast enough or come far enough with carbon capture to find any other realistic way around it,” he says.

The biggest threat to biodiversity is not climate change, but land use change. This photo from Borneo in Malaysia, where the rainforest is cut down to make room for palm oil plantations. Photo: Shutterstock, NTB

No way forward without support of the people

One of the major challenges is finding the balance between producing renewable energy and conserving nature. Both solar power and wind power require large tracts of land, which Norway has already run up against.

Climate measures impact our vulnerable environment.

Altered land use is already – without question – the biggest threat to biodiversity, according to a statement by the international nature panel IPBES a couple of years ago. Climate measures impact our vulnerable environment.

“We can hardly solve this issue without bringing wind and solar power offshore. We need huge amounts of renewable energy. But again, without the people affirming its legitimacy, this is practically impossible. These are questions that we can’t resolve without understanding the politics,” says Moe.

Of course we depend on technological progress to reach our goal, but this process will revolve at least as much around how we design good policy as around technology and economics,” Moe says.