European union’s ambitious climate goals are achievable – here’s how

Europe is well on its way to achieving its ambitious climate goals of a 55 per cent reduction in emissions in 2030 and “net zero” in 2050. But proposed policies must be implemented quickly and effectively.

Naysayers argue nothing can be done about climate change; action is too costly, disruptive, and technically challenging. Anarchists argue emissions are fault of the economic system so that we need to overthrow capitalism and degrow the economy to reduce emissions and achieve climate goals.

Europe may be about to prove both sides wrong.

Greenhouse gas emissions from European Union member states were 32.5% lower in 2022 than in 1990. In 2023, the EU managed a substantial emission reduction of five percentage points, according to projections from the Global Carbon Project, a research group.

This substantial emission reduction is the result both of climate policy progress and high energy prices following Russia’s war on the Ukraine.

If the EU successfully concludes and implements the European Commission’s climate policy proposals, it may be well on track to achieving its ambitious emissions targets of minus 55% in 2030 and net-zero in 2050.

- You might also like: The energy footprint of architecture built by oil

Unparalleled – but incomplete – progress

In its recent assessment of the European climate policy, the independent European Climate Advisory Board, which was created under the EU’s climate law of 2022, found the EU had made unparalleled but incomplete progress.

The board noted that agriculture was lagging behind, and has not managed to reduce emissions at all.

Industry, energy and agriculture all need substantial investments in installations that will have low operating costs and thus save money over time.

The assessment also identified further measures, such as phasing out fossil fuel subsidies and other economic incentives that favour resource overconsumption.

Late to the game – but not too late

Like the rest of the world, Europe has been late in understanding the depth of change needed to build a zero-carbon economy and plotting a course to reach that goal.

Past mistakes, such as dependency on cheap Russian gas and heavy investments in diesel engines rather than car battery technology, mean costly course corrections now.

Before 2019, the EU had put in place a general climate policy architecture, including an Emissions Trading System which put a price on emissions from large stationary polluters, national emission targets for buildings, transport and agriculture, and technology standards.

The carbon price was too low, and progress was piecemeal and always counteracted by policies in agriculture, transport, and industry which basically increased emissions.

Real leadership on climate goals

With the European Green Deal from 2020, under the impressive leadership of Ursula von der Leyen and supported by the European Parliament and Council, the Commission has undertaken comprehensive policy reform to address many emission sources and achieve climate goals.

Past mistakes need to be corrected now, but this will require confronting special interest groups who benefit from public largess.

Not all policy proposals have been approved yet, however, and many still need to be implemented by the member states. Implementation can be more or less ambitious, more or less effective, slow or fast.

The Climate Board has found that only a swift and effective implementation of the proposed policies will allow the EU to meet its emission target for 2030.

Successful completion of the European Green Deal, which is well under way, would demonstrate European leadership in addressing one of the fundamental challenges of our times and put pressure on other governments.

Can save tax money and the planet, too

What has struck me most in reviewing European climate policy is the persistence of policies that are both costly and cause emissions.

The European Court of Auditors has repeatedly criticized fossil fuel subsidies, which have not been reduced over the past decades. Further, tax breaks support excessive energy use, unsustainable agricultural practices, and large residences.

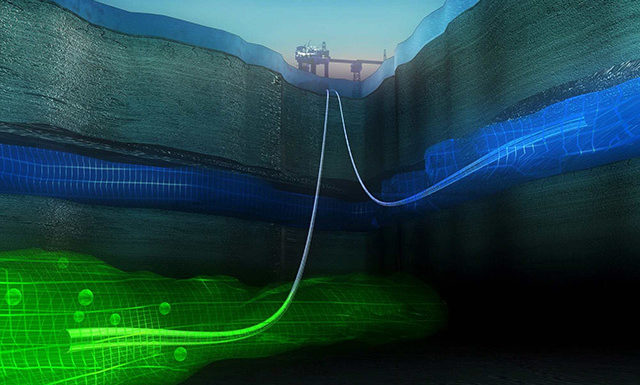

This is also a big problem in Norway, with its enormous subsidies for new oil production. And tax exemptions support energy use, meat production and large homes.

Why do our politicians feel that this is a good use of our tax money?

Sometimes fossil fuel subsidies and energy tax breaks also benefit less well-off parts of the population. In these cases, the board has recommended targeted policies be put in place to help people and businesses adjust.

These past mistakes need to be corrected now, but this will require confronting special interest groups who benefit from public largess.

Sometimes fossil fuel subsidies and energy tax breaks also benefit less well-off parts of the population. In these cases, the board has recommended targeted policies be put in place to help people and businesses to adjust.

Despair or indifference? There is a better alternative.

The transition to net-zero will need to continue after 2030.

Policy implementation is not at all trivial, from renovating an ageing housing stock to constructing the required electricity grid. But the fact that the crucial milestone of a 55% reduction is well in sight demonstrates the feasibility of moving away from fossil fuels.

By redoubling our efforts, rather than overthrowing the system or throwing up our hands in despair, we can solve one of the big challenges of our times.

Denying progress, as both activists and denialists are prone to do, falsely suggests that we are on the wrong course, when in fact we have finally begun to turn the ship around.

Edgar Hertwich, a member of the EUs Climate Advisory Board, is professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and currently a guest researcher at BOKU and IIASA.

This viewpoint was originally published in Norwegian in Dagens Næringsliv, a Norwegian national newspaper.