Second-hand clothing is good, but less is best

Norway will reap major environmental benefits if residents stop sending wearable clothes out of the country, according to a recent study on clothing consumption in Norwegian households.

The textile industry has a major impact on the environment, fuelled by people’s consumption habits and fast fashion with its frequent, new trends.

In Norway, the former model and actress Jenny Skavlan, the second-hand clothing sales site Tise and the Great Norwegian Sewing Bee (Symesterskapet) have helped focus more attention on reusing and repurposing clothes. This, along with the fact that more and more stores and brands offer a repair service for their products, suggests that a change may be on the horizon.

A new study from NTNU has thoroughly examined clothing consumption in Norwegian households. The study has analysed the materials used and the environmental consequences of all the life cycle stages until waste processing or export out of Norway.

One goal has been to investigate the possibility of more circular fashion on a national scale.

- You might also like: People over 60 are greenhouse gas emissions bad guys

From linear to circular fashion in Norway

“Clothing consumption in Norway is mainly linear, and most of the garments that are acquired are brand new and leave the system through incineration or export,” says Kamila Krych. Krych is a doctoral research fellow at NTNU’s Department of Energy and Process Engineering and the Industrial Ecology Programme.

Researchers have catalogued a huge range of environmental impacts that our clothes have from cradle to grave. Based on this, they have proposed an alternative circular approach involving a systematic transition to reuse and rental.

This is especially relevant now that the European Commission is proposing requirements regarding reductions in textile waste.

Advantages when second-hand and rented replace new

Krych is one of three researchers in the project, which has looked at the possible advantages of introducing a larger proportion of second-hand clothing into Norwegian households. This would be an alternative to sending the clothes out of the country or incinerating them, as is currently done with almost all unwanted clothing.

Where do our clothes actually come from? Researchers Kamila Krych and Johan Berg Pettersen have looked at this question from a large-scale perspective. Here they are studying the laundry tags on some second-hand clothes. Photo: Maren Agdestein/NTNU

“We asked ourselves: what if people wanted to get the same types of garments, but buy second-hand or rent them instead of buying new?” says Associate Professor Johan Berg Pettersen at the Industrial Ecology Programme.

A large proportion of the clothes that are currently thrown away are in good condition and could instead be reused in this country. In a circular clothing economy, these second-hand clothes would replace new clothes, and not just become an addition to our wardrobes, as is often the case today.

If people reuse and rent more, this will help reduce the need for new clothes. However, even in a circular clothing economy, the fact remains that new clothes have to be produced due to wear and tear.

“In an alternative scenario we have created for Norwegian households, an increase in the proportion of used or rented clothing from 5 per cent to 74 per cent would reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 57 per cent, the water footprint by 62 per cent and energy consumption by 47 per cent,” Krych said.

Making it possible to replace clothes as often as before

The researchers are fully aware that this scenario entails massive behavioural changes for Norwegian households. At the same time, this alternative allows the population to replace clothing at the same rate as today.

“We found that the circular alternative offers significant environmental benefits. These benefits can only be achieved when the circular system is correctly set up. We need to change our habits, what we throw away, and possibly amend relevant legislation, which together will maximize the benefits of a circular clothing system,” says Krych.

Krych says that “best” clothes, such as shirts and dresses worn for special occasions, are something that people seem more likely to want to rent than other types of clothing. Photo: Maren Agdestein/NTNU

The researchers concluded in their study that if climate and environmental impacts are to be reduced even more than this, people must buy fewer garments than they currently do. In other words, people need to buy less clothing.

How to analyse Norwegian clothing consumption

The researchers took 2018 as their starting point. They then collected data from a wide range of sources, including everything from imports, exports and Norwegian manufacturing, to clothing used by the private and public sectors, and the proportion of clothes that are purchased new as opposed to rented or bought second-hand.

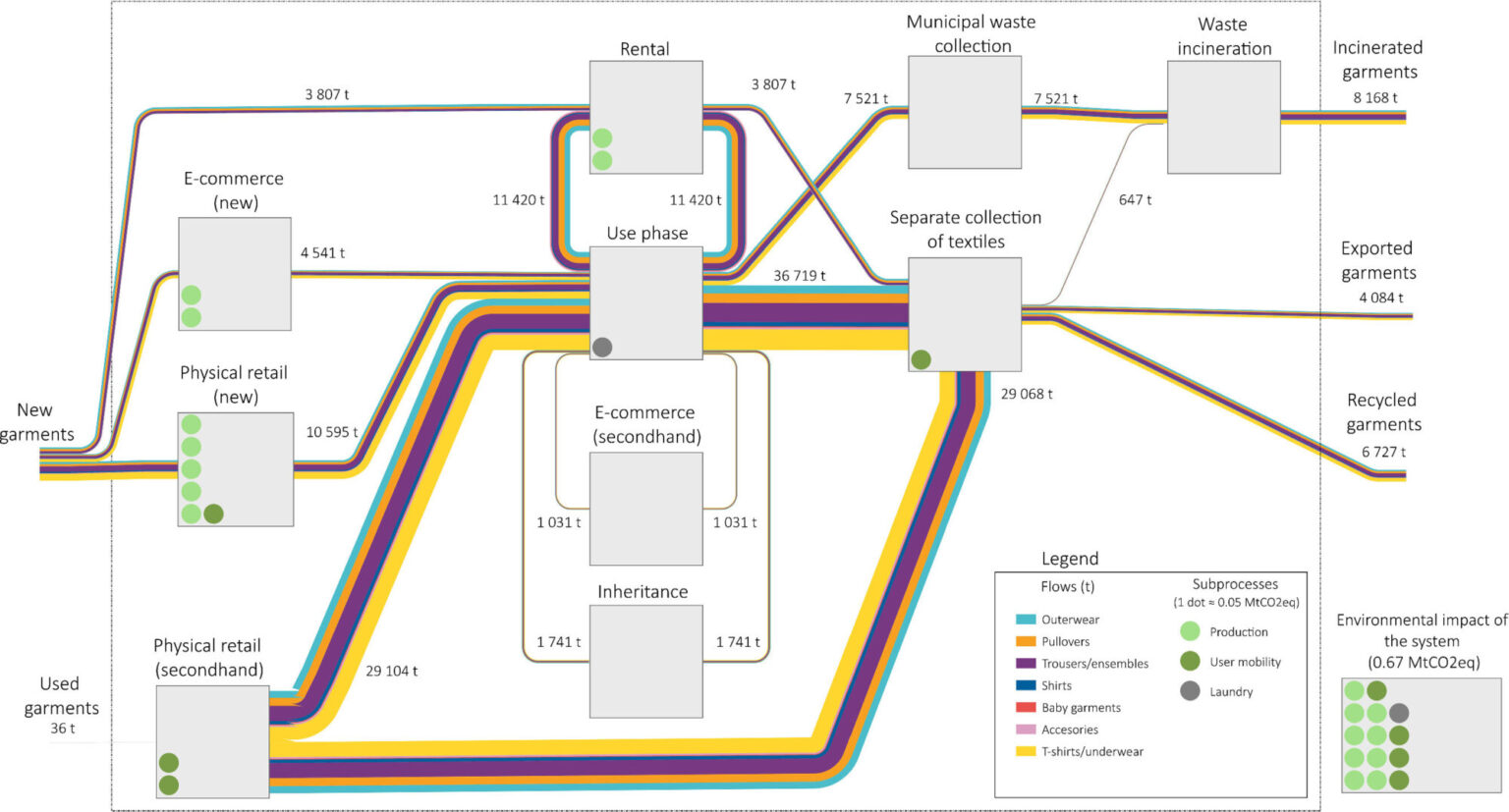

Clothing included in the study was outerwear, various types of sweaters, trousers, skirts, shorts, shirts, baby clothing, accessories such as gloves and scarves, and finally t-shirts and underwear.

The researchers used three environmental indicators were used in the study: CO2 equivalents, water consumption and energy use from both renewable and non-renewable sources. The researchers studied the manufacturing of clothes, the transportation of clothes from places like Shanghai to Oslo, how far customers may have travelled to pick up clothes from retail outlets, and energy use in shops and collection points.

To get an overview of how clothes are used in people’s homes, the researchers modelled how often clothes are washed, dried and ironed. They also considered emissions from incinerating old clothes.

Clothes retain their value

In their alternative scenario, the researchers introduced a high degree of clothing rental, taking into account research on the types of clothing that people tend to be interested in renting.

Naturally, few people want to rent underwear, while there is more interest in renting baby clothes.

In this circular scenario, the value of the clothes remains in the system longer through better waste sorting.

This diagram shows a model of a circular alternative to the clothing system in Norway in 2018. Grey boxes represent processes, and purple lines represent clothing flows.

The research has been supported by the Research Council of Norway through the Lasting project.

References:

Maria Corolina Mora_Sojo, Kamila Krych, Johan Berg Pettersen: Evaluating the current Norwegian clothing system and a circular alternative Resources, Conservation and Recycling, Volume 197, October 2023

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2023.107109