Eiderdown farming – a living cultural tradition

For centuries, perhaps millennia, people and birds have interacted with each other. The tradition of eiderdown harvesting from this northern duck is still practised.

In earlier times, collecting eggs and feathers from nests was common in Norway. This cultural tradition is still kept alive by locals and other enthusiasts.

Birgitta Berglund has studied eider down farming areas and the special culture along the Norwegian Helgeland coast since the 1970s. She is currently a professor in the Department of Archaeology and Cultural History at the NTNU University Museum.

“These coastal communities were important in earlier times,” says Berglund, who is still fascinated by the culture surrounding eider farming. She has spent a lot of time in the Vega Archipelago, including on Flovær, which is the archipelago’s outermost island.

People in the coastal villages have harvested eider duck eggs and down, and fished and hunted seals, but Berglund’s greatest interest lies with the practice of eider farming.

She has worked extensively with archaeological sites from the Iron Age and the Middle Ages in Tjøtta municipality and many other places on the Helgeland coast, as well as on Alstahaug and Sandnes farm sites near Sandnessjøen. The eider farms in the Vega Archipelago are some of her favourite locations for this traditional activity. She heads NTNU’s “down project” (Dunproskjektet), to which several institutions in Norway and Sweden have contributed.

- You might also like: What the Vikings put in their pillows

Old custom

Researchers with the down project are studying the down and feathers found in Norwegian and Swedish graves from the Nordic Iron Age, that is, from around 570 to 1030 CE. One goal is to determine which birds these finds originate from. The project is initially focused on the eider farms on the Helgeland coast, but the central Norwegian eider farms are also part of the study.

“The significance of the coastal communities in the Viking Age is evident from Egil’s Saga,” says Berglund.

The saga mentions that lendmann Thorolf Kveldulvsson from the Sandnes farmstead sent his people out to the egg nests – among other places – in the late 800s. Down from the eider nests was no doubt harvested at the same time.

The powerful seafarer Ottar from Hålogaland told King Alfred of Wessex in the late 800s that he lived further north than anyone else. He related that he received ten bags of down as part of the tax from the most distinguished Sami in the area. Ottar’s story was recorded and has been preserved.

Article continues below picture.

World heritage site

This tradition is still part of Norwegian culture in several places in Norway. Towards the end of the 1800s, an estimated 1 million eggs were likely harvested annually. Today, the traditions are carried on almost exclusively in northern Norway, in a controlled and much more limited form. Down harvesting has followed a similar trajectory.

Arvid Pedersen with down that he just collected from a nest under the shed. Photo: Birgitta Berglund, NTNU

“The eider harvesting and women’s contribution to the process was an important factor in the Vega Archipelago being added to UNESCO’s World Heritage List,” says Berglund.

The archipelago was listed in 2004. However, population decline and changing times have led to a steadily decreasing number of eider farms. But birdwatchers and the Nordland Ærfugllag (Nordland Eider Association) contribute to keeping the tradition alive on Helgeland. Although people no longer live on the farms year round, they come during spring and summer.

People have built houses and nests for the birds, called “e-houses” by the locals. They watch over the birds and nests in the spring and make sure that the adult birds and their young are doing well. People tie up their cats, and don’t allow children to play outdoors, according to a 1991 article by Berglund in the prehistory journal Spor. (You can download it here. See pages 34 to 37. In Norwegian.)

In return, the birds leave their valuable down, which people harvest as soon as the young and adult birds abandon their nests in the summer. The females pull the down from their body and push it into the nest to keep the eggs warm.

- You might also like: Uncovering the secrets of Arctic seabird colonies

Cleaning the down

An eiderdown cleaning harp is used to separate out the down from other nest materials. Photo: Birgitta Berglund, NTNU

People have also figured out how to make the job of cleaning the down a little easier by building the nests for the birds, rather than collecting the down from nests made by the ducks themselves.

“People like to use seaweed to make the nests. Down from this kind of nest is easier to clean,” Berglund says.

Eider ducks use grass and twigs when making their own nests, which makes it much harder to clean the down. The harvested down is cleaned through a process called “harping,” after first being picked through to separate out the impurities.

A down cleaning harp is a sieve-like tool that consists of a frame of stretched strings where you place the down. By moving a wooden stick across the strings, the impurities bounce out. You can see how this works in the video below, at around 1:16 into it

Article continues under the video.

Today, Utværet Lånan is the largest eiderdown producer. Previously, it belonged to the powerful Tjøtta estate. People living in the outlying communities were serfs of the estate until the beginning of the 20th century. A lot of manual work is still required to produce first-class eider down.

Culture and bird research

Berglund became interested in the eider farming culture back in 1972, when she was sent to the Helgeland coast to contribute to a research project as a newly arrived student in Norway.

Since then, her research has progressed in fits and starts, although not for any lack of willpower.

As Berglund explains, “Sometimes I’ve had people, but no money. Other times I’ve had money, but no people.”

The Research Council of Norway, the Norwegian Environment Agency, the North Trøndelag County Council and the NTNU University Museum have contributed to the financing of Dunproskjektet.

Right now, finding a method to definitively identify feathers is an important part of Berglund’s work. She has recently collaborated closely with postdoctoral fellow Jørgen Rosvold, who is actually a zoologist but also has archaeology training.

- You might also like: Why aren’t house sparrows as big as geese?

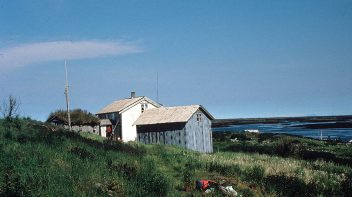

A lot of eider duck houses can be found on the island Heimlandet. Eider keepers build nests in both the overturned boat and the shed. Photo: Birgitta Berglund, NTNU

Still making down products

These days harvesting down isn’t always that lucrative an enterprise, since it is so labour intensive. But traditions are important, not least for people’s identity. Eiderdown duvets are still manufactured from the collected down.

“A nest yields about 16-17 grams of cleaned, dried down. A duvet requires 900 to 1000 grams of down. So we figure about 60 nests per finished duvet,” says Berglund.

These duvets are naturally expensive. You can probably count on an adult duvet costing you about NOK 40,000 to 50,000 today, but they are popular despite the price. They can even be made to order.

Berglund, of course, owns a real eiderdown duvet. Her husband visited Vega and gave it to her – and she loves it.