Finding ways to use less salt on snowy roads

It’s springtime in much of the northern hemisphere, although spring snowstorms are still possible. When that happens, salt trucks and ploughs help make roads safe. But road salt can be bad for the environment, and can rust cars, bicycles and other metal. New research shows that salt use can be safely — and substantially — cut in certain circumstances.

Road networks in different countries

- The US has 6,552,000 km of roads, of which 4,310,000 km are paved and 12,243,000 km are unpaved.

- The UK has 3,497 km of motorways and 344,000 km of paved roads.

- Norway has a road network of 92,946 kilometres, of which 72,033 kilometres are paved and 664 kilometres are motorway.

The UK uses about 2 million tonnes. And in the US, highway departments use a staggering 17 million tonnes of it.

Although these three countries have radically different climates, not to mention cumulative amounts of roads, the use of salt on roads and highways offers the same benefits and disadvantages.

Salt can melt snow and ice outright, which is called de-icing. It can prevent the formation of ice on the road, which is called anti-icing. It can also prevent snow from compacting into a hard layer, making it easier for ploughs to clear roadways, which is called anti-compaction. All those features help make roads safer for winter travel.

The Norwegian Public Roads Administration holds training sessions for contractors who maintain Norwegian roads. Here, researcher Henri Giudici explains how different concentrations of salt affect snow. Photo: Øystein Larsen, Statens Vegvesen.

The disadvantages are equally clear. Salt causes cars and bicycles to rust. It can pollute roadside soil, harm vegetation and enter waterways and groundwater. And it costs money.

All those factors and more set researcher Henri Giudici on a four-year odyssey to figure out just how much — or little — salt can be safely used on Norwegian roads during snowfall. The answer it turns out, is a lot less.

The Norwegian Public Roads Administration (NPRA), which funded Giudici’s PhD research, says his findings are instrumental in supporting guidelines that the agency issues to contractors who actually plough Norway’s roads.

“Each operator takes a decision during winter maintenance. … It is very tough, and it is very natural in that position to use more salt than needed.”

Bare road strategy

Before you can understand what Giudici found out, it’s helpful to understand how the authorities make decisions about ploughing and salt use overall.

Norway, like many other snowy countries, has some roads that it wants to keep as bare as possible, according to Kai Rune Lysbakken, senior principal engineer at the NPRA’s Directorate of Public Roads, in the Operation, Maintenance and Road Technology division.

“We have what we call the bare road strategy for some roads in Norway,” he said. “Those are the highly trafficked roads, about 20 per cent of the road network, where we use salt. On the other roads, we sometimes use salt during the transition periods of the year, in the spring and the autumn, when the temperatures are around 0 degrees C.”

Salt is often used preventatively at the beginning of a snowstorm on highly travelled roads, because it makes it easier for the ploughs to scrape snow off the asphalt. But more about that later.

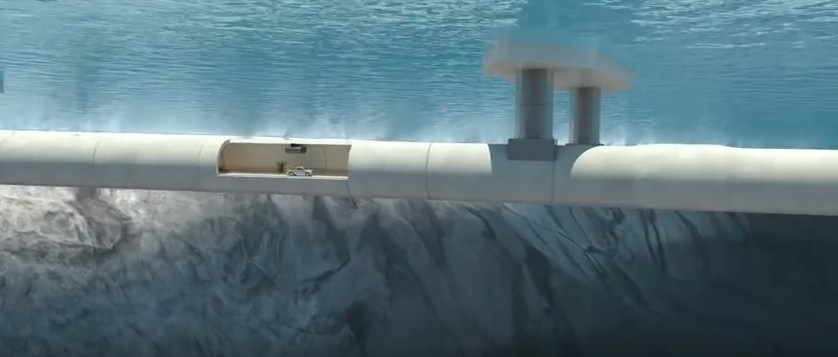

- You might also like: Basic safety measures will save lives in tunnels

Collaboration builds fundamental understanding

Giudici, who was awarded his PhD this spring from the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, is focused on one very important aspect of road salting: how salt affects the behaviour of snow when it is compacted by tyres.

While there is quite a bit of research using documented practical tests on salt spreading techniques, different chemicals and spreading rates, the collaboration between NTNU and NPRA looks at the underlying basic principles that control how salt behaves. The collaboration, called “Forskningssenter vinterdrift” (Winter Operations Research Centre) is “building basic knowledge on anti-icing, anti-compaction and anti-icing,” Lysbakken said.

Giudici used a high-speed camera along with the LARS testing facility to see how snow behaved when it contained different amounts of salt. Photo: Nancy Bazilchuk, NTNU

Giudici’s work was designed to study how salt affects the compacting process and how little diluted salt solution is enough to prevent snow compaction. He studied the period when most salt is used on the roads, during snowfalls.

“When snow begins to fall on a recently salted road, the snow will melt and the salt will be diluted,” he explained. “The process can continue until the salt reaches its melting capacity. The fallen snow mixes with the diluted salt solution and the presence of the diluted salt solution prevents the formation of bonds between the snow grains and between the snow and road surface.”

Salt use climbing

The NPRA’s Lysbakken says 70-80 per cent of all salt is used during snowfall in areas with lots of snow or in the south, where traffic levels are high.

He says Norway’s long-time policy is to use only as much salt as is necessary, to limit negative effects, while still using enough to make sure that people can drive safely and get to where they need to go.

The NPRA conducted a four-year comprehensive study of the environmental effects of salt called Salt SMART, which was completed in 2011. The study documented salt’s detrimental effects on lakes and aquifers and some types of roadside vegetation, and recommended strategies to cut use and protect vulnerable areas.

Use is climbing anyway, he said.

“There are several reasons for this,” he said. “The climate is changing, so we have more days with the temperatures around 0 degrees C where we have to use salt. And traffic in some areas has increased, which means we have to increase the use of salt in those areas.”

- You might also like: Speed warning saves lives and reduces emissions

Government guidelines on salt use

The NPRA doesn’t have its own fleet of snowploughs and salt sheds. Instead, in a system that started in 2003, the government lets out about 110 contracts for the whole of the country.

Lysbakken’s department develops the guidelines that tell contractors how much salt per square meter should be used for different classes of roads, and for different snow and ice conditions.

Salt use in Norway is climbing, and not just because climate change is making for more days that hover around freezing, the most challenging temperatures when it comes to snow on roads. One reason may be that road maintenance personnel may feel that it’s better to be safe than sorry and add more salt to reduce the risk of accidents. But research shows that above a certain level, salt doesn’t make the road any safer. Photo: NTB Scanpix/Shutterstock

For the 2017-2018 winter, which was extremely snowy in Norway, the country spent about NOK 2.5 billion on national and country winter road maintenance, including salt.

In spite of educational efforts to get contractors to use less salt, he said, “the increase in the use of salt has been higher than is justified by all these changing factors.”

Pricing mechanisms and the precautionary principal

Lysbakken thinks the trend for increased salt use above and beyond what might be expected is partly due to the pricing under the government’s contracting system.

But another factor is the precautionary principle, he thinks, where people who are on the ground, deciding how much salt to spread, would rather be safe than sorry.

“Each operator takes a decision during winter maintenance,” he said. “These people take a decision on a personal level about how much salt to use. It is very tough, and it is very natural in that position to use more salt than needed. If you get an accident on your ploughing route, that is very difficult.”

That is the importance of Giudici’s research, he said.

“We believe the use of salt is not optimal now, and that is where Henri’s work is quite important,” he said, because it provides solid science for the NPRA’s salt recommendation. That, he believes, should help persuade contractors they can safely use less.

120 kg of bagged snow and a freezing cold room

Giudici set about his task of determining just how much salt was needed by conducting two laboratory investigations and one field investigation.

Henri Giudici prepares to conduct a test outside, where he examined the difference between how much snow compacts with different salt concentrations. Photo: courtesy Henri Giudici

Some of the tests were conducted with human-made snow in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering’s Snow Lab. The lab contains a Linear Analyzer of Road Surface (LARS) laboratory, which is a room with a refrigerated eight-metre test track over which a free-rolling or braking tyre can travel as quickly as 10 m/second.

It also contains a snowmaking machine which Giudici used to make snow for his 2 laboratory investigations. The lab also has a high-speed digital camera, so researchers can watch what happens as the tyre drives over the snow on the test track.

Giudici prepared human-made snow and added different amounts of diluted salt solution different batches.

“In this way I was able to understand what is the minimum amount of diluted salt solution content that would ‘lubricate’ the contact bonds between ice particles and make these bonds weaker and easily destroyed,” he said.

One batch had 5 per cent by weight of diluted salt solution, another had 10 per cent, and the last batch had 40 per cent.

Then he rolled the tyre over the salty snow when the room was at -2 C, a temperature at which new snow can be most difficult and dangerous for driving.

He also conducted a field test, where he collected 120 kg of freshly fallen real snow and made different batches with the same amount by per cent weight of diluted salt solution in the test track. He then drove a car tyre over these different samples.

Making snow easy for ploughs to remove

What Giudici wanted to know was how salt affects the ability of freshly fallen snow to stick to the road after the snow has been compacted by cars.

Henri Giudici checks the screens at the LARS laboratory, where he was able to test how different salt solutions affect the ability of snow to stick to asphalt. Photo: Nancy Bazilchuk/NTNU

That matters because if the snow gets compacted by tyres and sticks firmly to the asphalt, a plough might not be able to scrape it off the road, and then the road will be slippery.

Salting the roads can reduce the strength of the compacted snow so that it is easy for ploughs to remove it. He found that it took just 5 per cent by weight of diluted salt solution (abbreviated wt % DSS) to make the snow so that ploughs could easily remove it.

Researcher Henri Giudici used this standard test tyre for his studies of how different salt solutions affected how well snow stuck to asphalt. Photo: Nancy Bazilchuk/NTNU

The most important thing his research showed was that if the amount of diluted salt solution added to the snow exceeded about 10 wt % DSS, it didn’t actually make the snow easier to remove by ploughs or by car tyres.

“There was a threshold over about 10 per cent,” he said. “Adding more didn’t really help.”

How much less salt?

Every snowfall is different, but consider this scenario:

The weather forecast calls for 5 cm of new snow of a specific density, and the temperature is -2 C.

Giudici said if we wanted to use salt to melt all this snow, it would take 168.2 grams per square metre of road to do the job. But to reach the 10 wt % DSS in snow, which is what Giudici discovered was enough to let car tyres to squish the snow off the road, you’d need just 18 grams per square meter of road.

“If you want salting to assist with ploughing, a 5 per cent salt solution, or 9 grams per square metre of road is enough,” he said. “This is the minimum, of course, because you will lose some salt during application.”

“Henri’s work mainly supports our guidelines, where we have gone from quite high rates to quite low rates during snowfalls,” the NPRA’s Lysbakken said. “Before we used to recommend 20-25 grams per square meter of road. Now we recommend a much lower dosage of just 5-10 grams. Now we can justify our salt specification regulations to use low spreading rates.”

Giudici also won the Young Professional Award from the PIARC-World Road Association at the XVth International Winter Road Congress in Gdansk in 2018.