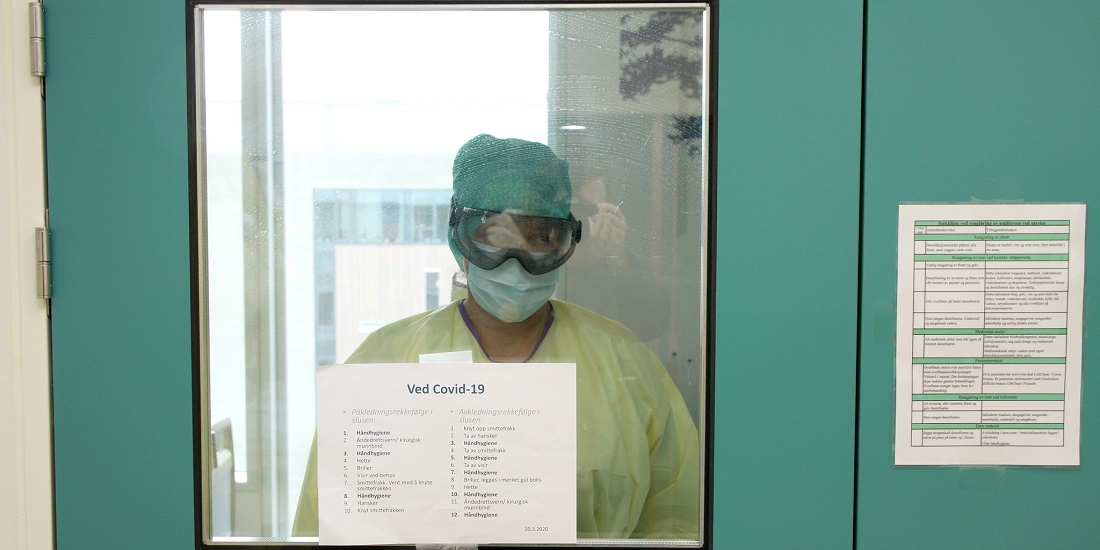

How are the busiest among us dealing with COVID-19?

COVID-19 has created an extra workload for people in socially critical professions. How does this added strain affect them and how do they handle it?

Workers in various occupations have been extra busy since the coronavirus pandemic struck. Employees in the health care system, the municipality, the police, the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration, the nursing and care sector, but also other professions are all among those affected.

Researchers at NTNU want to investigate how high workloads have impacted people in these critical occupations, and what coping strategies they have used to get through this hectic time.

- You might also like: Researchers find commonalities in all crises

Useful for later

“Gaining an understanding about the stresses that vulnerable groups are experiencing during and after the COVID-19 pandemic is important,” says Torhild Anita Sørengaard, a PhD candidate in NTNU’s Department of Psychology.

It is interesting to learn about various strategies that can reduce stress and prevent delayed negative effects, and the knowledge may come in handy later, during both this and future crisis situations.

“Safeguarding our human resources is especially important during COVID-19 to ensure that societal functions continue to work well during and after the crisis,” says Sørengaard.

How people respond to pressure and stress depends on their work environment and organization, along with their personal characteristics and strategies. Understanding about what eases the pressure can be used to prevent problems later.

- You might also like: Fast-moving information on a fast-moving virus

Many kinds of consequences

“Poor sleep, stress and burnout are widespread among workers with a high workload, and they can have negative consequences for the health and safety of people inside and outside the organization,” Sørengaard says.

Psychological stress and mental pressure at work are precursors to taking sick leave in the future, and are associated with burnout and sleep disorders. These strains have personal, organizational and socio-economic consequences.

Data collection will happen every three months starting at the end of May and will run until spring 2022. The first results from the research are expected this fall.