A policy that can increase the windfall profit of energy producers — like Russia

While former Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg steered Norway according to the logic of economics, today’s politicians seem to lack a basic understanding of markets. The result is a policy that amplifies energy scarcity and drives up energy prices – without policymakers recognizing this unintended consequence.

Multiple factors drove electricity prices sky high in Norway this winter: not much precipitation and low reservoirs in southern Norway, a reduced gas supply from Russia, the closure of nuclear power plants in Germany and Sweden, the need to repair reactors in Belgium and France, and rising cost of CO2 emissions allowances impacting coal power.

The Norwegian government’s subsidy scheme for household electricity use reduces consumers’ price sensitivity, leading consumers to use electricity without really worrying about how costly it is.

In a market economy, a shortfall in the supply of a product causes the price to rise until falling demand balances supply. A rising price also provides an incentive to increase production, but it takes years to build power plants, so we cannot expect electricity supply to increase over the short term.

The Norwegian government’s subsidy scheme for household electricity use reduces consumers’ price sensitivity, leading consumers to use electricity without really worrying about how costly it is. The Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation, NRK, even reported how one well-off Norwegian marvelled over how the government subsidy meant he could drive his two electric cars and heat his hot tub without cost.

“I think people who really needed this support should have gotten the help they needed,” Arild Grundetjern told NRK.

To balance supply and demand, the market price needs to be higher with a subsidy scheme than without, unless we limit energy use in other ways, by prohibiting unnecessary use, such as heating hot tubs.

The Norwegian government pays for the full cost of heating Arild Grundetjern’s hot tub, according to the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation, NRK.

Those who benefit most from a subsidy for electricity consumption are generators, who get what economists call a windfall profit. The ones who are affected the most are those who receive no or limited support, in this case businesses such as farmers and industrial companies. These individuals or groups will have higher energy prices than they would experience without a power support scheme.

- You might also like: Many reasons for war in Ukraine

Policy will increase energy poverty in Europe

Norway also trades electricity with neighbouring countries including Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK, to which it is connected to by sea cables. When subsidies reduce Norwegian consumers’ incentive to conserve energy, our trading partners will see increased prices. Rationing of electricity consumption is now taking place among low-income groups in Denmark and Germany, caused in part by Norwegian subsidies.

Edgar Hertwich , Director of the Industrial Ecology Programme at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and Member of the International Resource Panel at Green Week in Brussels in 2013. Photo: © EU – Patrick Mascar

Given that there is a shortage of supply, we can either use increased prices to create a new equilibrium between supply and demand, or we need to ration demand by limiting or shutting down certain uses. Politicians, rather than the market, then take on the task to determine which demand is allowed and which is forbidden. Do we really want that?

Gas scarcity is Russia’s design

Russia benefits a lot from the high energy prices and has helped to cause them. Gazprom, a Russian gas supplier to many European distributors in countries like Austria, reserved large storage capacities WITHOUT using them last year.

As a result, less gas was stored than in a normal year. Russia then reduced its gas deliveries. I don’t know if Gazprom had any intention of filling these reservoirs but was not allowed to, or if the company itself wanted to push up the price, given the planned shutdown of nuclear power and wrangling with the EU over long-term contracts versus spot markets.

- You might also like: Corruption almost inevitable in Russian businesses

Fuel tax cuts support Putin’s war

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has led to a near doubling of oil prices in a market that was already tight from renewed discipline in OPEC+, which includes Russia. Oil is Russia’s most important export commodity.

Now more people are demanding reduced taxes on transport fuels, and some governments such as Austria’s and Italy’s have instituted expensive schemes intended to reduce the energy costs to the consumer. In this way, people support the demand for oil, which increases oil prices further, and therefore Russia’s export revenues. That way, Putin profits from the invasion.

History repeats itself — maybe

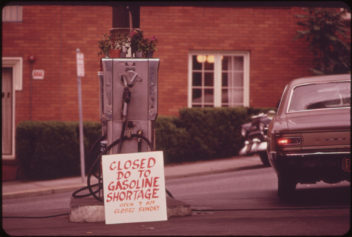

We’ve been here before. In 1973, Arab members of OPEC began an oil embargo of the United States as a sanction for Americas’ arms delivery to Israel after Egypt and Syria’s attack on Israel during the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur. President Nixon responded with price controls. The result was empty petrol pumps, long queues and rationing. Motorists were only allowed to fuel their cars on even or odd days, depending on their license plate. The intervention of politics in the market significantly exacerbated the shortages, and it became a major crisis.

David Falconer was commissioned by the US government to document the effects of the 1973 Oil Embargo on US citizens. Photo: David Falconer, US National Archives

In the longer run, European countries experienced a balance-of-payment crisis, to which they responded by increasing the taxation on fuel. People bought fuel-efficient cars. Taxation reduced the market power of OPEC because consumer states received a share of any price increase the cartel realized through reduced supply. Thus, it became less profitable for the cartel to cut production. It also reduced the exposure of consumer countries to the economic impact of supply rationing by OPEC. Conservation, including through high energy prices, was a highly effective response to supply restrictions and energy prices fell again. Couldn’t we learn from this?

- You might also like: Norway is the EU’s most integrated non-EU country

High energy consumption shouldn’t be rewarded

Many households must adapt to a changed price situation. I understand that people who struggled financially before the electricity crisis can no longer manage. In this case, it is appropriate for politicians respond to the extraordinary price rises and seek to support those in need. But the indiscriminate support of energy consumption, whether through electricity subsidies or reduced taxes, weakens the price signal and leads to higher inflation.

Politicians must be able to explain the situation and discuss the consequences of various alternatives of action.

Support for low-income groups and vulnerable industries should be independent of energy use. In this way, it will still pay for the person in question to reduce energy demand, whether through improved technology or change in behaviour. Without it, we will not strike a balance between supply and demand.

I doubt Jonas Gahr Støre wants to follow in Richard Nixon’s footsteps.

Energy policy in the 1970s, when angry oil producers stopped shipping oil to the United States, resulted in gas shortages. Photo: David Falconer, US National Archives

To avoid this, governments must not create expectations that are impossible to meet. Politicians must be able to explain the situation and discuss the consequences of various alternatives of action.

Today, Norway pursues a policy that results in a perverse outcome. An understanding of elementary energy economics suggests that the government should discontinue electricity and fuel subsidies and instead increase social payments unconnected to energy consumption levels for those in need.

A Norwegian version of the post was published in Dagens Næringsliv.