Listening to Leviathans

Nineteenth-century Norwegian technology helped bring large whale populations to the brink of extinction. Can 21st-century technology help save them?

It’s the summer of 2020, and two NTNU postdocs are scanning their computer screens while listening, intently, to the crackle and buzz of the files they are scanning.

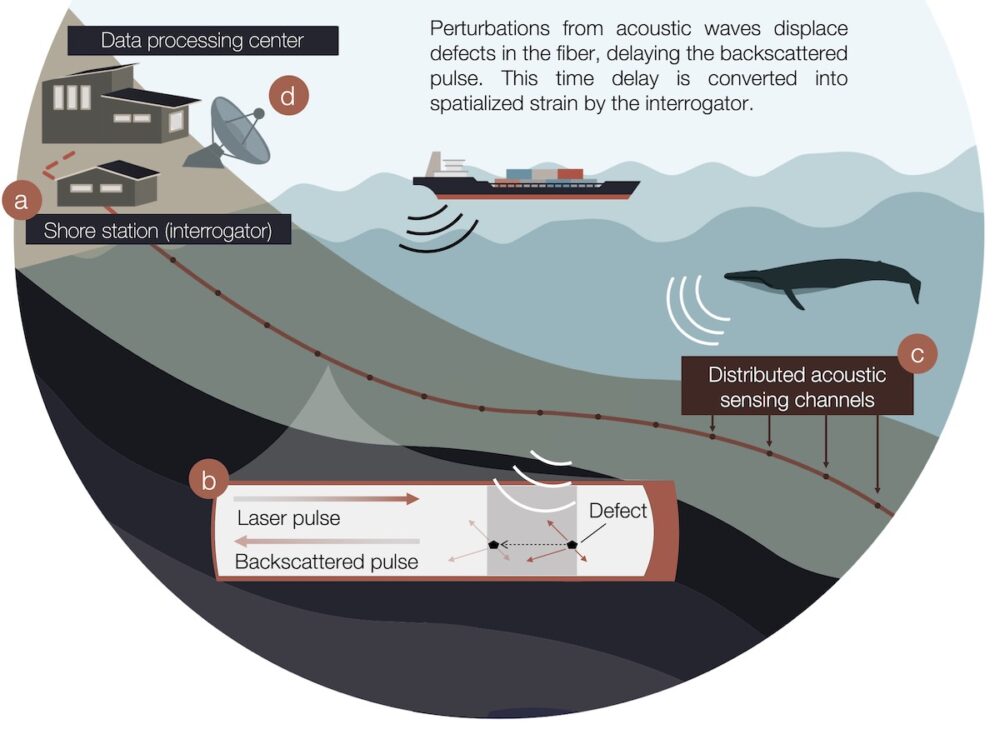

Each day, for 40 days, the two researchers, Léa Bouffaut and Hannah Joy Kriesell, are sent 7 terabytes of data from a remote research station in Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard. The data are from subsea fibre-optic cables strung between the station and Svalbard’s main town, Longyearbyen, roughly 120 km apart.

The two women part of a team that is trying to do something that has never been done before: to use the same subsea fibre-optic cables that are used for communication and the internet to eavesdrop on whales. The system is called Distributed Acoustic Sensing, or DAS.

I think it’s the first time that (this system) has been used to listen to blue whales.

The researchers were able to identify hundreds of different sounds, some of which were caused by storms, earthquakes and ships passing over or near the cable. But one day, Bouffaut, now at the K. Lisa Yang Center for Conservation Bioacoustics at Cornell University, hears what she has been hoping for.

“The day I knew I had a blue whale signal… I was just like, Well, that’s it. That’s it. That’s what we were looking for. This is my happiest day,” she said on the latest episode of 63 Degrees North, NTNU’s English-language podcast.

A big ocean and big animals

All told, the researchers were able to identify at least 830 different whale calls, said Martin Landrø, a professor in the Department of Electronic Systems, head of NTNU’s Centre for Geophysical Forecasting and who led the effort.

“I think it’s the first time that (this system) has been used to listen to blue whales,” he said.

The beauty of this research is that it demonstrates that the world’s more than 1.2 million kilometres of undersea fibre-optic cables could potentially be used to eavesdrop on whales across the planet, Bouffaut said.

That could help researchers understand how whales move across large stretches of the ocean in a way that is difficult to do now, she said.

Whale dialects and ship strikes

One NTNU researcher is also using her extensive library of whale sounds to help prevent ship-whale collisions in busy California shipping ports.

You want to make sure that if you’re telling ships that they need to slow down that there are whales there.

The west coast of California is home to the busiest port in all of the US, the Port of Los Angeles. It’s estimated that about 80 whales, mostly blue, fin and humpback whales, are killed every year in this area because of ship strikes. That may not seem like a lot, but there are only an estimated 10000 to 25000 blue whales in the whole world.

Ana Širović, an associate professor at NTNU’s Department of Biology, has an extensive library that includes Pacific ocean whale dialects.

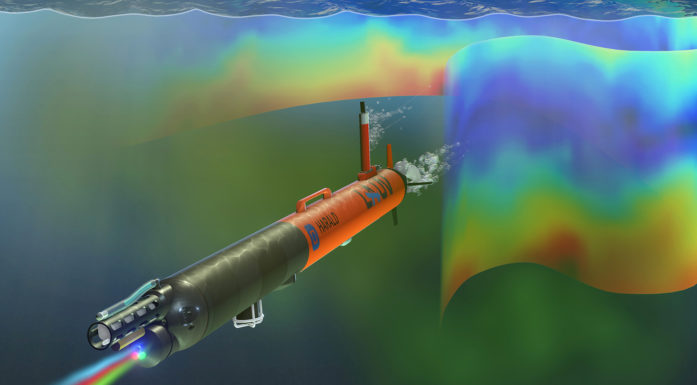

When she joined forces with the Whale Safe Project, Širović was able to work with other scientists who had developed buoys that send near real time data to provide information on presence of calling whales so that nearby ships can be alerted to slow down.

Avoiding false alarms

One of her key collaborators was Mark Baumgartner of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

“Mark had developed this tool that worked on the East Coast of the United States and while some of the species are similar on the west coast, the calls that they produce are very different, they each have their own dialect. So we had to adapt his AI tools, his automated detector tools to work on those new dialects,” she said on the podcast.

The system is still being perfected, Širović said, so that the information from the data is verified by an analyst to confirm that there is in fact, a whale present.

“We don’t want to be the boy who’s crying wolf, right? You want to make sure that if you’re telling ships that they need to slow down that there are whales there,” she said.

You can hear more about these projects, as well as the history of the 19th century Norwegian whaler whose technological innovations made whaling so devastatingly efficient, on this week’s episode.

References:

Landrø, M., Bouffaut, L., Kriesell, H.J. et al. Sensing whales, storms, ships and earthquakes using an Arctic fibre optic cable. Sci Rep 12, 19226 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23606-x

Léa Bouffaut, Kittinat Taweesintananon, Hannah Kriesell, Robin A Rørstadbotnen, John R Potter, Martin Landrø, Ståle E Johansen, Jan K Brenne, Aksel Haukanes, Olaf Schjelderup and Frode Storvik. Eavesdropping at the speed of light: distributed acoustic sensing of baleen whales in the Arctic. Frontiers in Marine Science. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.901348

Rørstadbotnen RA, Eidsvik J, Bouffaut L, Landrø M, Potter J, Taweesintananon K, Johansen S, Storevik F, Jacobsen J, Schjelderup O, Wienecke S, Johansen TA, Ruud BO, Wuestefeld A and Oye V (2023) Simultaneous tracking of multiple whales using two fiber-optic cables in the Arctic. Front. Mar. Sci. 10:1130898. DOI=10.3389/fmars.2023.1130898