Making the world’s fastest skis

They won’t feature at this year’s World Championships in Trondheim, but NTNU researchers believe the world’s fastest and most flexible cross-country skis will be ready for the 2027 World Championships in Falun.

This is the first winter season where it is illegal to use fluorinated ski wax in international cross-country, biathlon, Nordic combined and alpine skiing competitions. The reason for the ban is that fluorine is harmful to humans, animals and the environment.

The FramSki project at NTNU is a direct response to this, with researchers from three different fields working together to develop the world’s fastest cross-country skis. The experts involved are even talking about skis with customizable properties, i.e. skis that can be tailored in relation to both the individual skier’s personal preferences and the snow conditions on any given competition day.

Behind these ambitious goals are the Research Council of Norway, Olympiatoppen, the ski manufacturer Madshus, and the Brav Group. The latter owns Swix, the world’s largest producer of ski wax.

A brand new ski design

“This is about much more than just replacing fluorine molecules with other molecules in ski wax. We need to completely rethink how skis are designed,” explained Alex Klein-Paste, professor at NTNU’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

“We need to understand exactly how friction, or resistance, occurs under the skis. In addition, we need to understand how we can alter the surface structure of the ski base itself. We then need to figure out how to make glide wax products adhere as effectively as possible and last as long as possible.”

Tailor-made for NOK 30 million

Previously, researchers at NTNU have identified clear correlations between the basic design of a ski and its glide. The FramSki project is building on this knowledge, and the new ski will enable researchers to make individual adjustments to its properties.

Developing a new and completely superior ski is a world championship effort in its own right. To make sure they are first across the finishing line, the participants have invested NOK 30 million and partnered with three different research communities. The Research Council of Norway has provided half of the funding.

Macro, micro and nano

Researchers and PhD research fellows are working on three levels to develop new technology:

- The design and structure of the ski – macro

- The structure and surface chemistry of the ski base – micro

- Fluorine-free wax products – nano

At the Department of Chemistry, FramSki’s project manager Audun Formo Buene and PhD research fellow Silje Iren Strøm are working at the nano level to identify molecules that give the glide wax the strongest possible adhesion and durability.

At the Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering, Professor Martin Steinert and PhD research fellow Aleksander Auflem are exploring the microstructures to discover the formula for the smartest ski base.

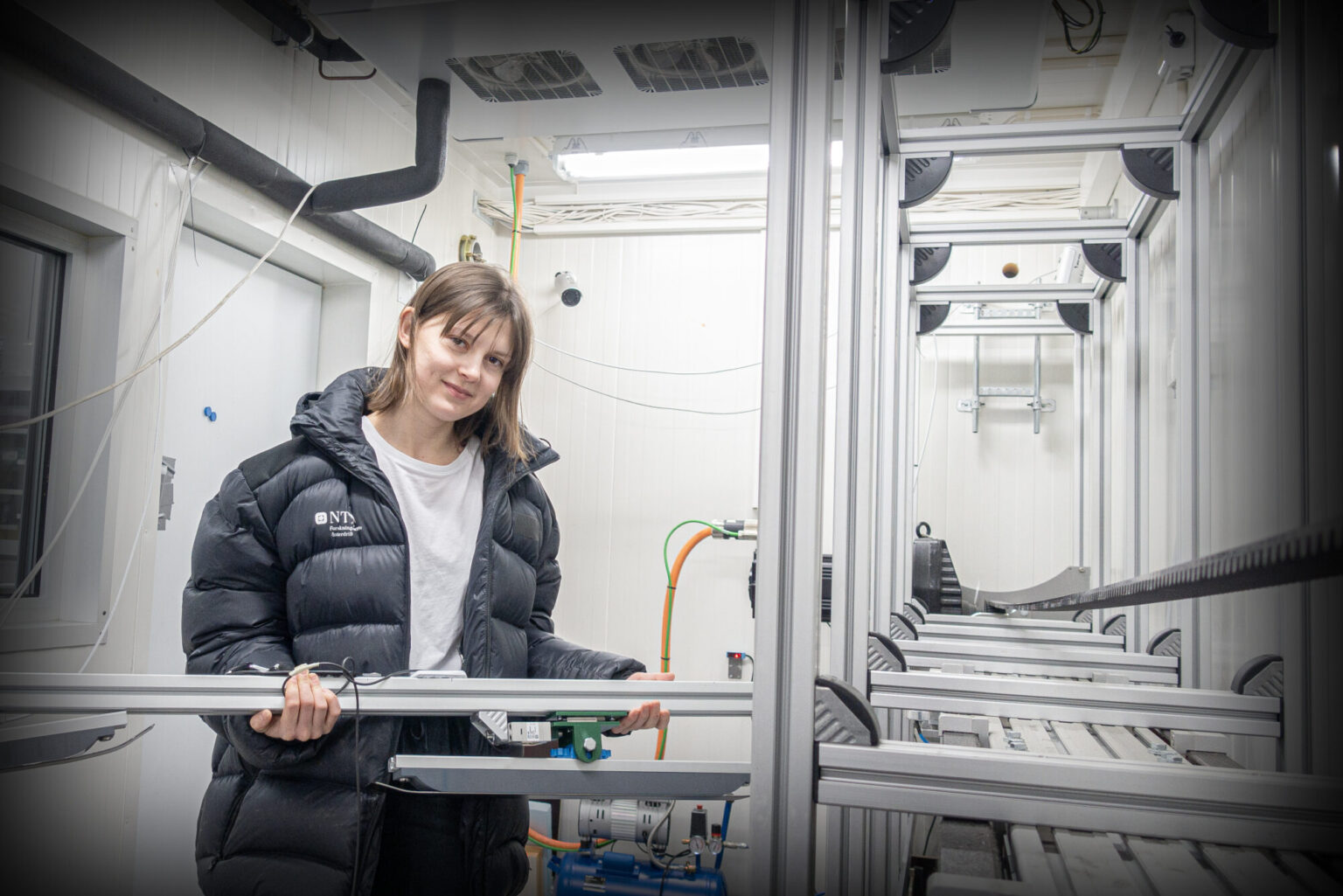

In the Snowlab at the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Alex Klein-Paste and PhD research fellow Johana Fialova are working on the design of the ski itself.

- You might also like: You too can save a few seconds on a short uphill sprint

The fluorine ban has been gradually implemented in recent years. Previously, fluorinated ski wax could compensate more for challenging snow conditions and ski bases that didn’t have an optimal surface.

“That is why we are now so focused on the structure of the ski base,” explained Alex Klein-Paste.

The reason for waxing failures lies in the base

According to Klein-Paste, what we in simple terms call a waxing failure – when skiers lose a race because the wax isn’t perfectly suited to the snow conditions – is actually a structural failure.

“The chances of waxing failures increase without fluorine. It is extremely challenging to find molecules that are as water-repellent and possess the same properties. There is a reason we have been using expensive fluorine-based products – they are simply technically superior. However, now we have to find alternatives,” explained the professor.

There are many people out there who are skilled at making, preparing and waxing skis. Many know what they are doing, but very few can explain why they are doing it. We are very interested in explaining why.

Gold medals and innovation

“We know that some people have this image of a group of crazy scientists in a basement at NTNU, doing revolutionary things to secure new gold medals for Norway. But that is not quite how it works,” he laughed.

Really?

“No. The interesting thing is the collaboration between ourselves and the industry that makes the skis. But it is ultimately the athletes and their tremendous efforts that produce the results. As researchers, we develop knowledge that provides the foundation for innovation, enabling the industry to be more competitive.”

Searching for the winning formula

The FramSki project is not the only initiative trying to find a winning fluorine-free formula. The NTNU researchers have colleagues and competitors, both at the University of Innsbruck in Austria and elsewhere around the world. Everyone is looking for the best solution.

“It is a competition, and of course, we hope we are the first to succeed. It will be important, especially for NTNU as a university, to show that we have contributed,” said Klein-Paste.

It all boils down to understanding exactly what happens the moment the ski base meets the snow. Klein-Paste describes what happens under the ski at that moment as incredibly exciting and highly complex.

Laser technology and sustainability

“There are many people out there who are skilled at making, preparing and waxing skis. Many know what they are doing, but very few can explain why they are doing it. We are very interested in explaining why,” Klein-Paste said.

The FramSki project is developing a new technology where lasers are being used to structure the ski base on a micro scale. The current method involves stone grinding. The project also aims to develop a permanent surface treatment for the ski. Another goal is to make the super skis easier to repair and recycle if they get damaged.

- You might also like: Researchers confirm that Johannes Høsflot Klæbo is the perfect skier for mass start races

Model skis

Researchers at NTNU Snowlab have developed model skis that enable them to identify, test and measure friction under different types of loads on various snow surfaces. Part of Johana Fialova’s work is to gain a full overview of what happens in the contact zones at the front and rear of the skis when they touch the snow. To understand as much as possible, she is going to test and measure the friction at the front and rear separately, and on different types of snow.

Johana Fialova, here in NTNU’s snow laboratory, will test the friction between fluorine-free skis and snow. The tribometer on the right measures that friction. The rig is made up of a friction meter with a nearly 9-meter-long track where a cart can accelerate up to 10 meters per second. The tests are recorded with a camera that captures 2,000 frames per second. Photo: Sølvi W. Normannsen.

This is relatively uncharted territory. Until now, most glide measurements and friction tests have been conducted along the entire length of the ski. The researchers explain that little is known about where the friction occurs, and it is therefore important to pinpoint exactly where along the ski base there is good glide and where it is lacking.

- You might also like: A future for skiing in a warmer world

User-oriented research

“This is what we are going to test, step by step. We are going to investigate three different surface structures against various types of snow,”said Fialova, who is excited to conduct research on something so closely related to the users.

FramSki is one of the Research Council of Norway’s Innovation Projects for the Industrial Sector. The goal is not just to win more Norwegian gold medals in skiing competitions; it is also about increasing Norwegian innovation, strengthening trade and industry, and securing jobs. When asked whether the super skis will be ready for the 2027 World Championships in Falun, researcher Klein-Paste answered with a resounding yes!