Predicted skewed waves – and found them

He solved a 127-year-old physics problem on paper and proved that off-centred boat wakes could exist. Five years later, practical experiments proved him right.

“Seeing the pictures appear on the computer screen was the best day at work I’ve ever had,” says Simen Ådnøy Ellingsen, an associate professor at NTNU’s Department of Energy and Process Engineering.

That was the day that PhD candidate Benjamin Keeler Smeltzer and master’s student Eirik Æsøy had shown in the lab that Ellingsen was right and sent him the photos from the experiment. Five years ago, Ellingsen had challenged accepted knowledge from 1887, armed with a pen and paper, and won.

He solved a problem regarding the so-called Kelvin angle in boat wakes, which has been unchallenged for 127 years. The boat wake is the v-shaped pattern that a boat or canoe makes when moving through the water. You’ve undoubtedly seen one at some point.

- You may also like: A new solution to an age-old equation can improve ship efficiency

39 degrees

It has long been assumed that the angle of the v-shaped wake behind a boat should always be just below 39 degrees, as long as the water isn’t too shallow. Regardless whether it’s behind a supertanker or a duck, this should always be true. Or not.

For like so many accepted facts, this turns out to be wrong, or at least not always the case. Ellingsen showed this.

“For me, it was a totally new field, and nobody told me it was hard,” Ellingsen explained when he first made his discovery.

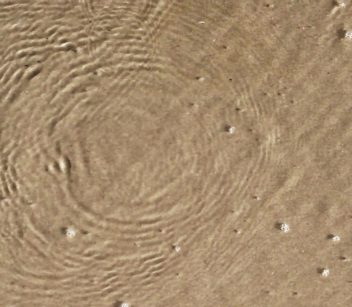

On the beach in the Netherlands in 2016. Oddly shaped rings. Is this the same effect we’re seeing? Here, a lot of different effects are at play. Photo: Simen Andreas Ådnøy Ellingsen, NTNU

Boat wakes can actually have a completely different angle under certain circumstances, and can even be off-centred with respect to the direction of the boat. This can happen when there are different currents in different layers of water, known as shear flow. For shear flow, Kelvin’s theory on boat wakes isn’t applicable.

“It took the genius of people like Cauchy, Poisson and Kelvin to solve these wave problems for the first time, even for the simplest case of still water without currents. It’s far easier for us to figure out the more general cases later, like we’ve done here, “ Ellingsen explains.

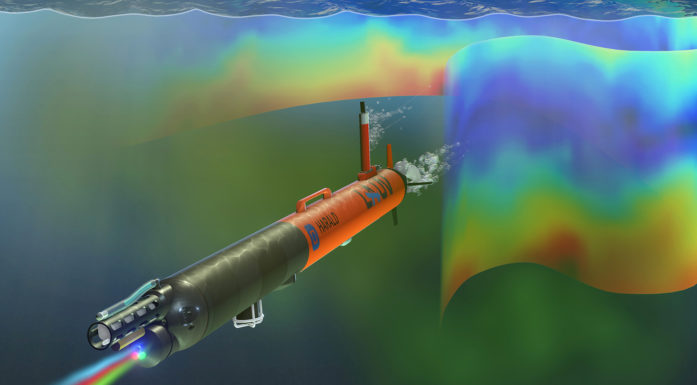

- You may also like: Ocean life in 3-D: Mapping phytoplankton with a smart AUV

Oblong rings

Ring waves also act funny under certain circumstances. If you throw a pebble in a lake on a peaceful summer’s day, the wave pattern will be perfect, concentric circles. But not if there’s shear flow. Then, the rings might turn into ovals.

Ellingsen also predicted this, expanding Cauchy and Poisson’s theory from 1815.

“After I did the first calculations, I was on a beach in the Netherlands watching the water flow back out after a wave. I made some rings in the water and took some photos. Looking at them later, the rings looked oblong to me, and I got pretty excited. That wasn’t science, of course, but now it is!” says Ellingsen.

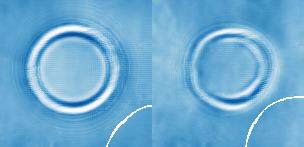

With no currents, ring waves are perfect circles. But with currents under the surface, the rings are oblong and off centre. Illustration: NTNU

Lab research backs up calculations

That was how Ellingsen ended up on the cover of the prestigious publication “Journal of Fluid Mechanics”. But all of his calculations had been done on paper, and had yet to be observed empirically.

Now, however, there’s lab research to back up his work, thanks to the PhD candidate and master’s student who were able to conduct experiments in a specially developed research tank, with Ellingsen as their supervisor.

Eirik Æsøy has a background as a technician, which saved time and money in building the lab. It took about six months to get everything up and running.

“Æsøy and I set up all the equipment to create the currents we needed,” Smeltzer explains.

Their results have also been published in the Journal of Fluid Mechanics.

“It’s pretty remarkable that the experiments from our little wave basin are being published there,” says Smeltzer.

The boat is moving at the same speed in all of these photos, 50 cm/s. According to Kelvin’s theory, all three of these wakes should look the same, but they don’t. Try to count the transverse waves behind the boat (the little white spot at the top of each image). Left: Skewed waves. Here, the surface is not moving, but there’s a current under the surface. Centre: Same speed, also with the surface at rest, but for this case there’s an underwater current against the direction of motion. Right: For this case, the boat and the underwater current are moving in the same direction, still with no surface motion. (This is shortly after the boat started moving, so you can see that the waves are closer together at the back). Illustration: NTNU

Practical uses

The results from their research on the Kelvin angle might have real practical consequences, such as potentially helping reduce fuel consumption in ships. A large portion of fuel on ships actually goes into making waves.

“Fuel consumption can double if the vessel is travelling downstream compared to upstream,” Ellingsen said.

These calculations are made based on currents at the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon in the USA. Here the currents are strong and the boats many.

So research on boats and ships in different currents is important for anyone interested in reducing fuel consumption and consequently, emissions.

This video shows what their research is about. In this case, Fr = 0.4 means that the boat model is moving at 40 cm/s, Fr = 0.5 means 50 cm/s, and so on. At these speeds, the little 10 cm long boat model becomes a realistic scale model of a full-sized ship. The surface of the water wasn’t initially moving, but there’s a current just under the surface. The current is also a realistic scale of something you’d see in a tidal river delta. The mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon has conditions like this, and is heavily trafficked, so it’s a good source of data for their research. The surface is actually in motion there as well, but that’s easy to correct for.

Boat wake in front of the boat

Ellingsen insists their results do not disprove Kelvin’s theory, only extend it. Kelvin’s angle still holds true as long as there are no current layers under the surface when the water is deep.

But as soon as there’s movement between layers of water, so that different layers move at different speeds, the angle changes. Sometimes by a lot. In theory, with extremely strong currents moving perpendicular to the direction of the boat, the wake can actually end up in front of the boat on one side.

“Then you should probably go sailing somewhere else,” says Ellingsen.

Sources:

Observation of surface wave patterns modified by sub-surface shear currents. Journal of Fluid Mechanics. Benjamin K. Smeltzer, Eirik Æsøy og Simen Å. Ellingsen. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2019.424

Further reading:

Theoretical research on boat wakes.(First paper, since further expanded.)