Need to know much more about deep sea mining

The Norwegian government has proposed opening an area of the continental shelf to deep sea mining. NTNU researchers have worked for more than a decade on this issue. They say we have much to learn before Norway can decide if this can become a viable industry.

On June 20th, the Norwegian government presented its plans for commercial seabed mineral mining on the Norwegian continental shelf. You can read the government’s press release and the white paper (only in Norwegian) on deep seabed mineral mining.

Research groups at NTNU have been working on this topic for more than a decade. Interdisciplinary research teams have looked at technological, geological, social, ethical and environmental aspects through the NTNU Oceans pilot programme on deep-sea mining, among others.

This research project is headed by Professor Steinar Løve Ellefmo. He has the following comments on the government’s plans:

“Society needs minerals. Deep-sea mineral mining must be regarded as a ‘source’ along with recycling and reuse, reduced consumption and onshore mineral mining. This is the best way to ensure coordinated, holistic management of our mineral resources.

The time is more than ripe to find out whether underwater mineral mining can be done responsibly. We have been working on this for many years, and this work should continue.

Allowing mineral activities on the Norwegian continental shelf will also increase the opportunities for collecting the data we need for good decision-making in the future about whether to go ahead with mining.

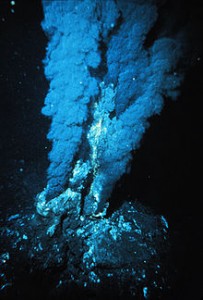

Deep sea minerals are found in the areas around undersea volcanoes, called black smokers. Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

Numerous technological concepts have been proposed, but none of the technologies have undergone full-scale testing. Work is now being done on this, and opening Norwegian waters for mineral activities will enable the necessary testing of both mining technologies and environmental monitoring technologies, for example.

Norway has many years of experience in marine operations, and over the decades the country has developed a sound resource management system with strict environmental legislation.

Prior to any start-up of operations and extraction, we need to collect additional data to characterize deep-sea ecosystems and geological structures, as well as to describe and assess possible consequences of deep-sea mining.

By taking these necessary management-related steps, Norway will be in a good position to demonstrate what sound management of mineral resources on the seabed actually entails.

NTNU has been working on marine mineral extraction from an interdisciplinary perspective for a number of years and will continue to do so through the TripleDeep project, for example. NTNU will be able to contribute valuable knowledge and expertise in connection with any award of mining licences.”

Concerned about political haste

The main objective of the TripleDeep project is to investigate whether deep-sea mining can be developed as a new source of critically important minerals in a sustainable way. The TripleDeep Project Group is a multidisciplinary team consisting of historians, marine biologists, economists, geologists and engineers, including Steinar Ellefmo.

The research project is headed by Professor Mats Ingulstad. Here’s what he had to say about the government’s decision to allow deep sea mineral mining:

“The TripleDeep project is still relatively young, and we consequently can’t give any clear answesr as to whether seabed mining can be carried out in a sustainable way. The issues are too broad and complex, and the knowledge gaps are still too great.

What worries me personally, as someone who researches the political economy of natural resources, is that the government has not taken this complexity seriously enough. The political haste and Norway’s decision to go it alone are incompatible with the precautionary principle.

There is also a lack of recognition that environmental problems – and their solutions – require a very broad-based approach with extensive international collaboration on research and resource management.

Not only do we currently know far too little about the conditions at the bottom of the ocean, we also know nothing about how this industry might affect us on land. What new vulnerabilities might this kind of mining unleash – in terms of environmental impacts, in value chains, and in international politics – for Norway and for the rest of the world?

The areas around the warm waters from the black smokers contain a completely unique — and mostly unknown — ecosystem. Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

Reference is often made to the fact that Norway has a great deal of experience in making money from commercial activities at sea. Before allowing any commercial operations, there should be a minimum requirement that the state invests some of the profits from the oil and gas industry, through the Research Council of Norway or other channels, to ensure the establishment of a solid knowledge base.

The fact that there is uncertainty regarding the relevance of a tax on ground rent income is just one of many indications of the lack of both hard knowledge and political understanding of the issues. There is a need for much more research, with a very broad approach, at NTNU and elsewhere.

If history can teach us anything, it is that allowing new types of business activities in unknown waters will give rise to a multitude of unforeseen challenges. It is essential to be properly prepared, and today we are not.”

Read more about: TripleDeep — The Deep Dilemmas: Deep Sea Mining for the new Deep Transition

Now is not the time to start mining

“The overall verdict from NTNU’s experts on the government’s public consultation is that there is so much uncertainty, especially in terms of the potential effects on ecosystems, that now is definitely not the time to start mining, and perhaps not even to allow commercial exploration as is currently being done,” says Siri Granum Carson, director of NTNU Oceans.

Formed by underwater volcanoes

Minerals on the seabed are found along the mid-ocean ridges where the tectonic plates meet in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. These are areas with high volcanic activity, most of which takes place at depths of several thousand metres. In places where the Earth’s crust has split open, openings form and seawater seeps down several kilometres into the Earth’s mantle. In geology, this process is called hydrothermal activity.

This water is heated up to temperatures of about 400 °C by liquid magma, and is then shot up again in an underwater geyser called a hydrothermal vent. The seawater extracts minerals and metals from the crust and brings them up to the seabed. When this superheated water comes into contact with cold water, metals including gold and silver, copper and cobalt, zinc and lead are deposited on the ocean floor.

The minerals we currently mine on land were formed by these same processes. The metal ore deposits in Sulitjelma, Kongsberg and Røros were under water some 500 million years ago.